I built this guide because I could never quite wrap my head around Makefiles. They seemed awash with hidden rules and esoteric symbols, and asking simple questions didn’t yield simple answers. To solve this, I sat down for several weekends and read everything I could about Makefiles. I've condensed the most critical knowledge into this guide. Each topic has a brief description and a self contained example that you can run yourself.

If you mostly understand Make, consider checking out the Makefile Cookbook, which has a template for medium sized projects with ample comments about what each part of the Makefile is doing.

Good luck, and I hope you are able to slay the confusing world of Makefiles!

Getting Started

Why do Makefiles exist?

Makefiles are used to help decide which parts of a large program need to be recompiled. In the vast majority of cases, C or C++ files are compiled. Other languages typically have their own tools that serve a similar purpose as Make. Make can also be used beyond compilation too, when you need a series of instructions to run depending on what files have changed. This tutorial will focus on the C/C++ compilation use case.

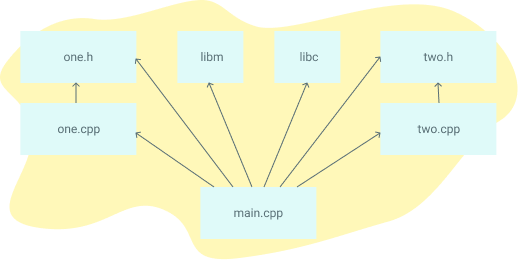

Here's an example dependency graph that you might build with Make. If any file's dependencies changes, then the file will get recompiled:

What alternatives are there to Make?

Popular C/C++ alternative build systems are SCons, CMake, Bazel, and Ninja. Some code editors like Microsoft Visual Studio have their own built in build tools. For Java, there's Ant, Maven, and Gradle. Other languages like Go and Rust have their own build tools.

Interpreted languages like Python, Ruby, and Javascript don't require an analogue to Makefiles. The goal of Makefiles is to compile whatever files need to be compiled, based on what files have changed. But when files in interpreted languages change, nothing needs to get recompiled. When the program runs, the most recent version of the file is used.

The versions and types of Make

There are a variety of implementations of Make, but most of this guide will work on whatever version you're using. However, it's specifically written for GNU Make, which is the standard implementation on Linux and MacOS. All the examples work for Make versions 3 and 4, which are nearly equivalent other than some esoteric differences.

Running the Examples

To run these examples, you'll need a terminal and "make" installed. For each example, put the contents in a file called Makefile, and in that directory run the command make. Let's start with the simplest of Makefiles:

hello:

echo "Hello, World"Note: Makefiles must be indented using TABs and not spaces or

makewill fail.

Here is the output of running the above example:

$ make

echo "Hello, World"

Hello, WorldThat's it!

Makefile Syntax

A Makefile consists of a set of rules. A rule generally looks like this:

targets: prerequisites

command

command

command- The targets are file names, separated by spaces. Typically, there is only one per rule.

- The commands are a series of steps typically used to make the target(s). These need to start with a tab character, not spaces.

- The prerequisites are also file names, separated by spaces. These files need to exist before the commands for the target are run. These are also called dependencies

The essence of Make

Let's start with a hello world example:

hello:

echo "Hello, World"

echo "This line will always print, because the file hello does not exist."There's already a lot to take in here. Let's break it down:

- We have one target called

hello - This target has two commands

- This target has no prerequisites

We'll then run make hello. As long as the hello file does not exist, the commands will run. If hello does exist, no commands will run.

It's important to realize that I'm talking about hello as both a target and a file. That's because the two are directly tied together. Typically, when a target is run (aka when the commands of a target are run), the commands will create a file with the same name as the target. In this case, the hello target does not create the hello file.

Let's create a more typical Makefile - one that compiles a single C file. But before we do, make a file called blah.c that has the following contents:

// blah.c

int main() { return 0; }Then create the Makefile (called Makefile, as always):

blah:

cc blah.c -o blahThis time, try simply running make. Since there's no target supplied as an argument to the make command, the first target is run. In this case, there's only one target (blah). The first time you run this, blah will be created. The second time, you'll see make: 'blah' is up to date. That's because the blah file already exists. But there's a problem: if we modify blah.c and then run make, nothing gets recompiled.

We solve this by adding a prerequisite:

blah: blah.c

cc blah.c -o blahWhen we run make again, the following set of steps happens:

- The first target is selected, because the first target is the default target

- This has a prerequisite of

blah.c - Make decides if it should run the

blahtarget. It will only run ifblahdoesn't exist, orblah.cis newer thanblah

This last step is critical, and is the essence of make. What it's attempting to do is decide if the prerequisites of blah have changed since blah was last compiled. That is, if blah.c is modified, running make should recompile the file. And conversely, if blah.c has not changed, then it should not be recompiled.

To make this happen, it uses the filesystem timestamps as a proxy to determine if something has changed. This is a reasonable heuristic, because file timestamps typically will only change if the files are modified. But it's important to realize that this isn't always the case. You could, for example, modify a file, and then change the modified timestamp of that file to something old. If you did, Make would incorrectly guess that the file hadn't changed and thus could be ignored.

Whew, what a mouthful. Make sure that you understand this. It's the crux of Makefiles, and might take you a few minutes to properly understand. Play around with the above examples or watch the video above if things are still confusing.

More quick examples

The following Makefile ultimately runs all three targets. When you run make in the terminal, it will build a program called blah in a series of steps:

- Make selects the target

blah, because the first target is the default target blahrequiresblah.o, so make searches for theblah.otargetblah.orequiresblah.c, so make searches for theblah.ctargetblah.chas no dependencies, so theechocommand is run- The

cc -ccommand is then run, because all of theblah.odependencies are finished - The top

cccommand is run, because all theblahdependencies are finished - That's it:

blahis a compiled c program

blah: blah.o

cc blah.o -o blah # Runs third

blah.o: blah.c

cc -c blah.c -o blah.o # Runs second

# Typically blah.c would already exist, but I want to limit any additional required files

blah.c:

echo "int main() { return 0; }" > blah.c # Runs firstIf you delete blah.c, all three targets will be rerun. If you edit it (and thus change the timestamp to newer than blah.o), the first two targets will run. If you run touch blah.o (and thus change the timestamp to newer than blah), then only the first target will run. If you change nothing, none of the targets will run. Try it out!

This next example doesn't do anything new, but is nontheless a good additional example. It will always run both targets, because some_file depends on other_file, which is never created.

some_file: other_file

echo "This will always run, and runs second"

touch some_file

other_file:

echo "This will always run, and runs first"Make clean

clean is often used as a target that removes the output of other targets, but it is not a special word in Make. You can run make and make clean on this to create and delete some_file.

Note that clean is doing two new things here:

- It's a target that is not first (the default), and not a prerequisite. That means it'll never run unless you explicitly call

make clean - It's not intended to be a filename. If you happen to have a file named

clean, this target won't run, which is not what we want. See.PHONYlater in this tutorial on how to fix this

some_file:

touch some_file

clean:

rm -f some_fileVariables

Variables can only be strings. You'll typically want to use :=, but = also works. See Variables Pt 2.

Here's an example of using variables:

files := file1 file2

some_file: $(files)

echo "Look at this variable: " $(files)

touch some_file

file1:

touch file1

file2:

touch file2

clean:

rm -f file1 file2 some_fileSingle or double quotes have no meaning to Make. They are simply characters that are assigned to the variable. Quotes are useful to shell/bash, though, and you need them in commands like printf. In this example, the two commands behave the same:

a := one two # a is assigned to the string "one two"

b := 'one two' # Not recommended. b is assigned to the string "'one two'"

all:

printf '$a'

printf $bReference variables using either ${} or $()

x := dude

all:

echo $(x)

echo ${x}

# Bad practice, but works

echo $x Targets

The all target

Making multiple targets and you want all of them to run? Make an all target.

Since this is the first rule listed, it will run by default if make is called without specifying a target.

all: one two three

one:

touch one

two:

touch two

three:

touch three

clean:

rm -f one two three

Multiple targets

When there are multiple targets for a rule, the commands will be run for each target. $@ is an automatic variable that contains the target name.

all: f1.o f2.o

f1.o f2.o:

echo $@

# Equivalent to:

# f1.o:

# echo f1.o

# f2.o:

# echo f2.o

Automatic Variables and Wildcards

* Wildcard

Both * and % are called wildcards in Make, but they mean entirely different things. * searches your filesystem for matching filenames. I suggest that you always wrap it in the wildcard function, because otherwise you may fall into a common pitfall described below.

# Print out file information about every .c file

print: $(wildcard *.c)

ls -la $?* may be used in the target, prerequisites, or in the wildcard function.

Danger: * may not be directly used in a variable definitions

Danger: When * matches no files, it is left as it is (unless run in the wildcard function)

thing_wrong := *.o # Don't do this! '*' will not get expanded

thing_right := $(wildcard *.o)

all: one two three four

# Fails, because $(thing_wrong) is the string "*.o"

one: $(thing_wrong)

# Stays as *.o if there are no files that match this pattern :(

two: *.o

# Works as you would expect! In this case, it does nothing.

three: $(thing_right)

# Same as rule three

four: $(wildcard *.o)% Wildcard

% is really useful, but is somewhat confusing because of the variety of situations it can be used in.

- When used in "matching" mode, it matches one or more characters in a string. This match is called the stem.

- When used in "replacing" mode, it takes the stem that was matched and replaces that in a string.

%is most often used in rule definitions and in some specific functions.

See these sections on examples of it being used:

Automatic Variables

There are many automatic variables, but often only a few show up:

hey: one two

# Outputs "hey", since this is the target name

echo $@

# Outputs all prerequisites newer than the target

echo $?

# Outputs all prerequisites

echo $^

touch hey

one:

touch one

two:

touch two

clean:

rm -f hey one two

Fancy Rules

Implicit Rules

Make loves c compilation. And every time it expresses its love, things get confusing. Perhaps the most confusing part of Make is the magic/automatic rules that are made. Make calls these "implicit" rules. I don't personally agree with this design decision, and I don't recommend using them, but they're often used and are thus useful to know. Here's a list of implicit rules:

- Compiling a C program:

n.ois made automatically fromn.cwith a command of the form$(CC) -c $(CPPFLAGS) $(CFLAGS) $^ -o $@ - Compiling a C++ program:

n.ois made automatically fromn.ccorn.cppwith a command of the form$(CXX) -c $(CPPFLAGS) $(CXXFLAGS) $^ -o $@ - Linking a single object file:

nis made automatically fromn.oby running the command$(CC) $(LDFLAGS) $^ $(LOADLIBES) $(LDLIBS) -o $@

The important variables used by implicit rules are:

CC: Program for compiling C programs; defaultccCXX: Program for compiling C++ programs; defaultg++CFLAGS: Extra flags to give to the C compilerCXXFLAGS: Extra flags to give to the C++ compilerCPPFLAGS: Extra flags to give to the C preprocessorLDFLAGS: Extra flags to give to compilers when they are supposed to invoke the linker

Let's see how we can now build a C program without ever explicitly telling Make how to do the compililation:

CC = gcc # Flag for implicit rules

CFLAGS = -g # Flag for implicit rules. Turn on debug info

# Implicit rule #1: blah is built via the C linker implicit rule

# Implicit rule #2: blah.o is built via the C compilation implicit rule, because blah.c exists

blah: blah.o

blah.c:

echo "int main() { return 0; }" > blah.c

clean:

rm -f blah*Static Pattern Rules

Static pattern rules are another way to write less in a Makefile, but I'd say are more useful and a bit less "magic". Here's their syntax:

targets...: target-pattern: prereq-patterns ...

commandsThe essence is that the given target is matched by the target-pattern (via a % wildcard). Whatever was matched is called the stem. The stem is then substituted into the prereq-pattern, to generate the target's prereqs.

A typical use case is to compile .c files into .o files. Here's the manual way:

objects = foo.o bar.o all.o

all: $(objects)

# These files compile via implicit rules

foo.o: foo.c

bar.o: bar.c

all.o: all.c

all.c:

echo "int main() { return 0; }" > all.c

%.c:

touch $@

clean:

rm -f *.c *.o allHere's the more efficient way, using a static pattern rule:

objects = foo.o bar.o all.o

all: $(objects)

# These files compile via implicit rules

# Syntax - targets ...: target-pattern: prereq-patterns ...

# In the case of the first target, foo.o, the target-pattern matches foo.o and sets the "stem" to be "foo".

# It then replaces the '%' in prereq-patterns with that stem

$(objects): %.o: %.c

all.c:

echo "int main() { return 0; }" > all.c

%.c:

touch $@

clean:

rm -f *.c *.o allStatic Pattern Rules and Filter

While I introduce functions later on, I'll foreshadow what you can do with them. The filter function can be used in Static pattern rules to match the correct files. In this example, I made up the .raw and .result extensions.

obj_files = foo.result bar.o lose.o

src_files = foo.raw bar.c lose.c

all: $(obj_files)

# Note: PHONY is important here. Without it, implicit rules will try to build the executable "all", since the prereqs are ".o" files.

.PHONY: all

# Ex 1: .o files depend on .c files. Though we don't actually make the .o file.

$(filter %.o,$(obj_files)): %.o: %.c

echo "target: $@ prereq: $<"

# Ex 2: .result files depend on .raw files. Though we don't actually make the .result file.

$(filter %.result,$(obj_files)): %.result: %.raw

echo "target: $@ prereq: $<"

%.c %.raw:

touch $@

clean:

rm -f $(src_files)Pattern Rules

Pattern rules are often used but quite confusing. You can look at them as two ways:

- A way to define your own implicit rules

- A simpler form of static pattern rules

Let's start with an example first:

# Define a pattern rule that compiles every .c file into a .o file

%.o : %.c

$(CC) -c $(CFLAGS) $(CPPFLAGS) $< -o $@Pattern rules contain a '%' in the target. This '%' matches any nonempty string, and the other characters match themselves. ‘%’ in a prerequisite of a pattern rule stands for the same stem that was matched by the ‘%’ in the target.

Here's another example:

# Define a pattern rule that has no pattern in the prerequisites.

# This just creates empty .c files when needed.

%.c:

touch $@Double-Colon Rules

Double-Colon Rules are rarely used, but allow multiple rules to be defined for the same target. If these were single colons, a warning would be printed and only the second set of commands would run.

all: blah

blah::

echo "hello"

blah::

echo "hello again"Commands and execution

Command Echoing/Silencing

Add an @ before a command to stop it from being printed

You can also run make with -s to add an @ before each line

all:

@echo "This make line will not be printed"

echo "But this will"Command Execution

Each command is run in a new shell (or at least the effect is as such)

all:

cd ..

# The cd above does not affect this line, because each command is effectively run in a new shell

echo `pwd`

# This cd command affects the next because they are on the same line

cd ..;echo `pwd`

# Same as above

cd ..; \

echo `pwd`

Default Shell

The default shell is /bin/sh. You can change this by changing the variable SHELL:

SHELL=/bin/bash

cool:

echo "Hello from bash"Double dollar sign

If you want a string to have a dollar sign, you can use $$. This is how to use a shell variable in bash or sh.

Note the differences between Makefile variables and Shell variables in this next example.

make_var = I am a make variable

all:

# Same as running "sh_var='I am a shell variable'; echo $sh_var" in the shell

sh_var='I am a shell variable'; echo $$sh_var

# Same as running "echo I am a amke variable" in the shell

echo $(make_var)Error handling with -k, -i, and -

Add -k when running make to continue running even in the face of errors. Helpful if you want to see all the errors of Make at once.

Add a - before a command to suppress the error

Add -i to make to have this happen for every command.

one:

# This error will be printed but ignored, and make will continue to run

-false

touch one

Interrupting or killing make

Note only: If you ctrl+c make, it will delete the newer targets it just made.

Recursive use of make

To recursively call a makefile, use the special $(MAKE) instead of make because it will pass the make flags for you and won't itself be affected by them.

new_contents = "hello:\n\ttouch inside_file"

all:

mkdir -p subdir

printf $(new_contents) | sed -e 's/^ //' > subdir/makefile

cd subdir && $(MAKE)

clean:

rm -rf subdir

Export, environments, and recursive make

When Make starts, it automatically creates Make variables out of all the environment variables that are set when it's executed.

# Run this with "export shell_env_var='I am an environment variable'; make"

all:

# Print out the Shell variable

echo $$shell_env_var

# Print out the Make variable

echo $(shell_env_var)The export directive takes a variable and sets it the environment for all shell commands in all the recipes:

shell_env_var=Shell env var, created inside of Make

export shell_env_var

all:

echo $(shell_env_var)

echo $$shell_env_varAs such, when you run the make command inside of make, you can use the export directive to make it accessible to sub-make commands. In this example, cooly is exported such that the makefile in subdir can use it.

new_contents = "hello:\n\techo \$$(cooly)"

all:

mkdir -p subdir

printf $(new_contents) | sed -e 's/^ //' > subdir/makefile

@echo "---MAKEFILE CONTENTS---"

@cd subdir && cat makefile

@echo "---END MAKEFILE CONTENTS---"

cd subdir && $(MAKE)

# Note that variables and exports. They are set/affected globally.

cooly = "The subdirectory can see me!"

export cooly

# This would nullify the line above: unexport cooly

clean:

rm -rf subdirYou need to export variables to have them run in the shell as well.

one=this will only work locally

export two=we can run subcommands with this

all:

@echo $(one)

@echo $$one

@echo $(two)

@echo $$two.EXPORT_ALL_VARIABLES exports all variables for you.

.EXPORT_ALL_VARIABLES:

new_contents = "hello:\n\techo \$$(cooly)"

cooly = "The subdirectory can see me!"

# This would nullify the line above: unexport cooly

all:

mkdir -p subdir

printf $(new_contents) | sed -e 's/^ //' > subdir/makefile

@echo "---MAKEFILE CONTENTS---"

@cd subdir && cat makefile

@echo "---END MAKEFILE CONTENTS---"

cd subdir && $(MAKE)

clean:

rm -rf subdirArguments to make

There's a nice list of options that can be run from make. Check out --dry-run, --touch, --old-file.

You can have multiple targets to make, i.e. make clean run test runs the clean goal, then run, and then test.

Variables Pt. 2

Flavors and modification

There are two flavors of variables:

- recursive (use

=) - only looks for the variables when the command is used, not when it's defined. - simply expanded (use

:=) - like normal imperative programming -- only those defined so far get expanded

# Recursive variable. This will print "later" below

one = one ${later_variable}

# Simply expanded variable. This will not print "later" below

two := two ${later_variable}

later_variable = later

all:

echo $(one)

echo $(two)Simply expanded (using :=) allows you to append to a variable. Recursive definitions will give an infinite loop error.

one = hello

# one gets defined as a simply expanded variable (:=) and thus can handle appending

one := ${one} there

all:

echo $(one)?= only sets variables if they have not yet been set

one = hello

one ?= will not be set

two ?= will be set

all:

echo $(one)

echo $(two)Spaces at the end of a line are not stripped, but those at the start are. To make a variable with a single space, use $(nullstring)

with_spaces = hello # with_spaces has many spaces after "hello"

after = $(with_spaces)there

nullstring =

space = $(nullstring) # Make a variable with a single space.

all:

echo "$(after)"

echo start"$(space)"endAn undefined variable is actually an empty string!

all:

# Undefined variables are just empty strings!

echo $(nowhere)Use += to append

foo := start

foo += more

all:

echo $(foo)String Substitution is also a really common and useful way to modify variables. Also check out Text Functions and Filename Functions.

Command line arguments and override

You can override variables that come from the command line by using override.

Here we ran make with make option_one=hi

# Overrides command line arguments

override option_one = did_override

# Does not override command line arguments

option_two = not_override

all:

echo $(option_one)

echo $(option_two)List of commands and define

The define directive is not a function, though it may look that way. I've seen it used so infrequently that I won't go into details, but it's mainly used for defining canned recipes and also pairs well with the eval function.

define/endef simply creates a variable that is assigned to a list of commands. Note here that it's a bit different than having a semi-colon between commands, because each is run in a separate shell, as expected.

one = export blah="I was set!"; echo $$blah

define two

export blah="I was set!"

echo $$blah

endef

all:

@echo "This prints 'I was set'"

@$(one)

@echo "This does not print 'I was set' because each command runs in a separate shell"

@$(two)Target-specific variables

Variables can be assigned for specific targets

all: one = cool

all:

echo one is defined: $(one)

other:

echo one is nothing: $(one)Pattern-specific variables

You can assign variables for specific target patterns

%.c: one = cool

blah.c:

echo one is defined: $(one)

other:

echo one is nothing: $(one)Conditional part of Makefiles

Conditional if/else

foo = ok

all:

ifeq ($(foo), ok)

echo "foo equals ok"

else

echo "nope"

endifCheck if a variable is empty

nullstring =

foo = $(nullstring) # end of line; there is a space here

all:

ifeq ($(strip $(foo)),)

echo "foo is empty after being stripped"

endif

ifeq ($(nullstring),)

echo "nullstring doesn't even have spaces"

endifCheck if a variable is defined

ifdef does not expand variable references; it just sees if something is defined at all

bar =

foo = $(bar)

all:

ifdef foo

echo "foo is defined"

endif

ifndef bar

echo "but bar is not"

endif

$(makeflags)

This example shows you how to test make flags with findstring and MAKEFLAGS. Run this example with make -i to see it print out the echo statement.

bar =

foo = $(bar)

all:

# Search for the "-i" flag. MAKEFLAGS is just a list of single characters, one per flag. So look for "i" in this case.

ifneq (,$(findstring i, $(MAKEFLAGS)))

echo "i was passed to MAKEFLAGS"

endifFunctions

First Functions

Functions are mainly just for text processing. Call functions with $(fn, arguments) or ${fn, arguments}. You can make your own using the call builtin function. Make has a decent amount of builtin functions.

bar := ${subst not, totally, "I am not superman"}

all:

@echo $(bar)

If you want to replace spaces or commas, use variables

comma := ,

empty:=

space := $(empty) $(empty)

foo := a b c

bar := $(subst $(space),$(comma),$(foo))

all:

@echo $(bar)Do NOT include spaces in the arguments after the first. That will be seen as part of the string.

comma := ,

empty:=

space := $(empty) $(empty)

foo := a b c

bar := $(subst $(space), $(comma) , $(foo))

all:

# Output is ", a , b , c". Notice the spaces introduced

@echo $(bar)

String Substitution

$(patsubst pattern,replacement,text) does the following:

"Finds whitespace-separated words in text that match pattern and replaces them with replacement. Here pattern may contain a ‘%’ which acts as a wildcard, matching any number of any characters within a word. If replacement also contains a ‘%’, the ‘%’ is replaced by the text that matched the ‘%’ in pattern. Only the first ‘%’ in the pattern and replacement is treated this way; any subsequent ‘%’ is unchanged." (GNU docs)

The substitution reference $(text:pattern=replacement) is a shorthand for this.

There's another shorthand that that replaces only suffixes: $(text:suffix=replacement). No % wildcard is used here.

Note: don't add extra spaces for this shorthand. It will be seen as a search or replacement term.

foo := a.o b.o l.a c.o

one := $(patsubst %.o,%.c,$(foo))

# This is a shorthand for the above

two := $(foo:%.o=%.c)

# This is the suffix-only shorthand, and is also equivalent to the above.

three := $(foo:.o=.c)

all:

echo $(one)

echo $(two)

echo $(three)The foreach function

The foreach function looks like this: $(foreach var,list,text). It converts one list of words (separated by spaces) to another. var is set to each word in list, and text is expanded for each word.

This appends an exclamation after each word:

foo := who are you

# For each "word" in foo, output that same word with an exclamation after

bar := $(foreach wrd,$(foo),$(wrd)!)

all:

# Output is "who! are! you!"

@echo $(bar)The if function

if checks if the first argument is nonempty. If so runs the second argument, otherwise runs the third.

foo := $(if this-is-not-empty,then!,else!)

empty :=

bar := $(if $(empty),then!,else!)

all:

@echo $(foo)

@echo $(bar)The call function

Make supports creating basic functions. You "define" the function just by creating a variable, but use the parameters $(0), $(1), etc. You then call the function with the special call function. The syntax is $(call variable,param,param). $(0) is the variable, while $(1), $(2), etc. are the params.

sweet_new_fn = Variable Name: $(0) First: $(1) Second: $(2) Empty Variable: $(3)

all:

# Outputs "Variable Name: sweet_new_fn First: go Second: tigers Empty Variable:"

@echo $(call sweet_new_fn, go, tigers)The shell function

shell - This calls the shell, but it replaces newlines with spaces!

all:

@echo $(shell ls -la) # Very ugly because the newlines are gone!Other Features

Include Makefiles

The include directive tells make to read one or more other makefiles. It's a line in the makefile that looks like this:

include filenames...This is particularly useful when you use compiler flags like -M that create Makefiles based on the source. For example, if some c files includes a header, that header will be added to a Makefile that's written by gcc. I talk about this more in the Makefile Cookbook

The vpath Directive

Use vpath to specify where some set of prerequisites exist. The format is vpath <pattern> <directories, space/colon separated><pattern> can have a %, which matches any zero or more characters.

You can also do this globallyish with the variable VPATH

vpath %.h ../headers ../other-directory

some_binary: ../headers blah.h

touch some_binary

../headers:

mkdir ../headers

blah.h:

touch ../headers/blah.h

clean:

rm -rf ../headers

rm -f some_binary

Multiline

The backslash ("\") character gives us the ability to use multiple lines when the commands are too long

some_file:

echo This line is too long, so \

it is broken up into multiple lines.phony

Adding .PHONY to a target will prevent Make from confusing the phony target with a file name. In this example, if the file clean is created, make clean will still be run. Technically, I should have have used it in every example with all or clean, but I didn't to keep the examples clean. Additionally, "phony" targets typically have names that are rarely file names, and in practice many people skip this.

some_file:

touch some_file

touch clean

.PHONY: clean

clean:

rm -f some_file

rm -f clean.delete_on_error

The make tool will stop running a rule (and will propogate back to prerequisites) if a command returns a nonzero exit status.DELETE_ON_ERROR will delete the target of a rule if the rule fails in this manner. This will happen for all targets, not just the one it is before like PHONY. It's a good idea to always use this, even though make does not for historical reasons.

.DELETE_ON_ERROR:

all: one two

one:

touch one

false

two:

touch two

falseMakefile Cookbook

Let's go through a really juicy Make example that works well for medium sized projects.

The neat thing about this makefile is it automatically determines dependencies for you. All you have to do is put your C/C++ files in the src/ folder.

# Thanks to Job Vranish (https://spin.atomicobject.com/2016/08/26/makefile-c-projects/)

TARGET_EXEC := final_program

BUILD_DIR := ./build

SRC_DIRS := ./src

# Find all the C and C++ files we want to compile

# Note the single quotes around the * expressions. Make will incorrectly expand these otherwise.

SRCS := $(shell find $(SRC_DIRS) -name '*.cpp' -or -name '*.c' -or -name '*.s')

# String substitution for every C/C++ file.

# As an example, hello.cpp turns into ./build/hello.cpp.o

OBJS := $(SRCS:%=$(BUILD_DIR)/%.o)

# String substitution (suffix version without %).

# As an example, ./build/hello.cpp.o turns into ./build/hello.cpp.d

DEPS := $(OBJS:.o=.d)

# Every folder in ./src will need to be passed to GCC so that it can find header files

INC_DIRS := $(shell find $(SRC_DIRS) -type d)

# Add a prefix to INC_DIRS. So moduleA would become -ImoduleA. GCC understands this -I flag

INC_FLAGS := $(addprefix -I,$(INC_DIRS))

# The -MMD and -MP flags together generate Makefiles for us!

# These files will have .d instead of .o as the output.

CPPFLAGS := $(INC_FLAGS) -MMD -MP

# The final build step.

$(BUILD_DIR)/$(TARGET_EXEC): $(OBJS)

$(CXX) $(OBJS) -o $@ $(LDFLAGS)

# Build step for C source

$(BUILD_DIR)/%.c.o: %.c

mkdir -p $(dir $@)

$(CC) $(CPPFLAGS) $(CFLAGS) -c $< -o $@

# Build step for C++ source

$(BUILD_DIR)/%.cpp.o: %.cpp

mkdir -p $(dir $@)

$(CXX) $(CPPFLAGS) $(CXXFLAGS) -c $< -o $@

.PHONY: clean

clean:

rm -r $(BUILD_DIR)

# Include the .d makefiles. The - at the front suppresses the errors of missing

# Makefiles. Initially, all the .d files will be missing, and we don't want those

# errors to show up.

-include $(DEPS)