1. Introduction

Matplotlib is the most popular plotting library in python. Using matplotlib,

you can create pretty much any type of plot. However, as your plots get more

complex, the learning curve can get steeper.

The goal of this tutorial is to make you understand ‘how plotting with

matplotlib works’ and make you comfortable to build full-featured plots with

matplotlib.

2. A Basic Scatterplot

The following piece of code is found in pretty much any python code that has

matplotlib plots.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

matplotlib.pyplot is usually imported as plt. It is

the core object that contains the methods to create all sorts of charts and

features in a plot.

The %matplotlib inline is a jupyter notebook specific command that let’s you

see the plots in the notbook itself.

Suppose you want to draw a specific type of plot, say a scatterplot, the

first thing you want to check out are the methods under plt (type

plt and hit tab or type dir(plt) in python

prompt).

Let’s begin by making a simple but full-featured scatterplot and take it from

there. Let’s see what plt.plot() creates if you an arbitrary

sequence of numbers.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

# Plot

plt.plot([1,2,3,4,10])

#> [<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x10edbab70>]

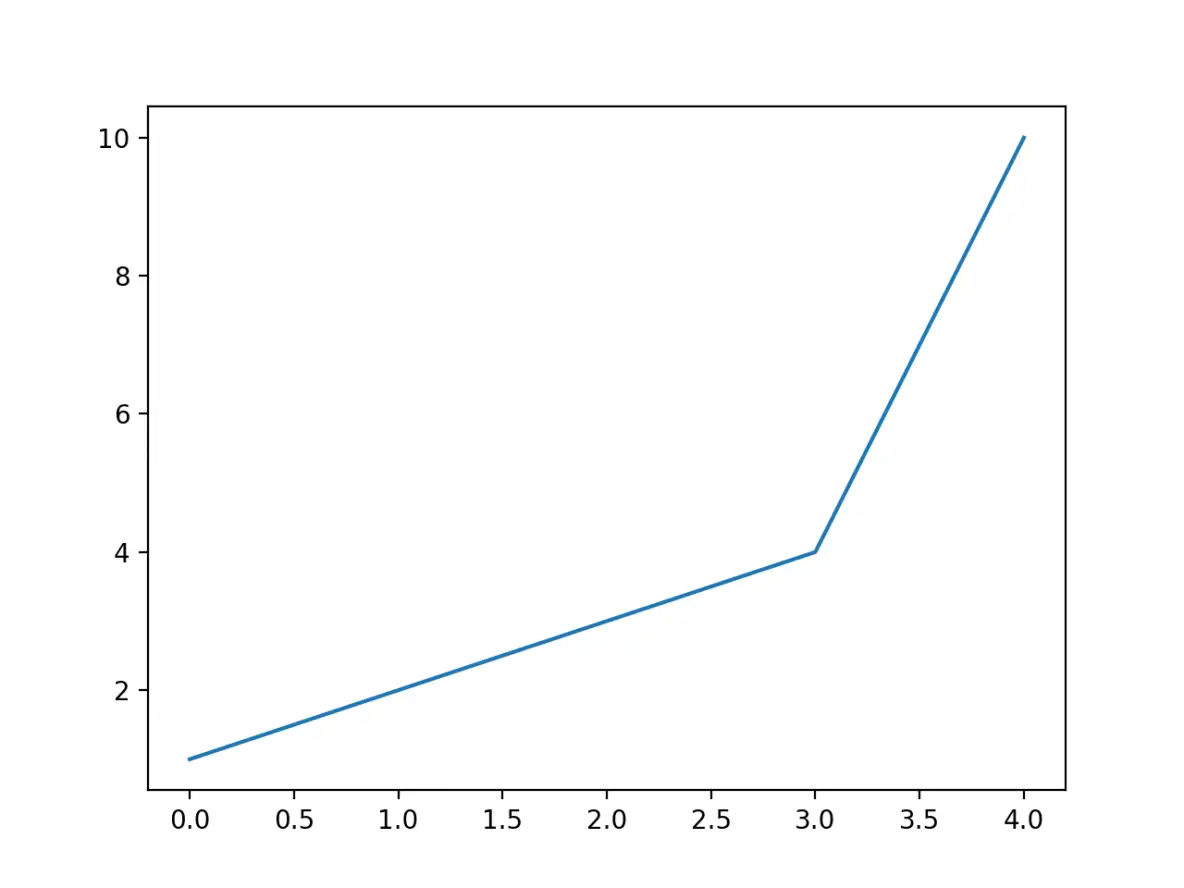

I just gave a list of numbers to plt.plot() and it drew a line

chart automatically. It assumed the values of the X-axis to start from zero

going up to as many items in the data.

Notice the line matplotlib.lines.Line2D in code output?

That’s because Matplotlib returns the plot object itself besides drawing the

plot.

If you only want to see the plot, add plt.show() at the end and

execute all the lines in one shot.

Alright, notice instead of the intended scatter plot, plt.plot

drew a line plot. That’s because of the default behaviour.

So how to draw a scatterplot instead?

Well to do that, let’s understand a bit more about what arguments

plt.plot() expects. The plt.plot accepts 3 basic

arguments in the following order: (x, y, format).

This format is a short hand combination of

{color}{marker}{line}.

For example, the format 'go-' has 3 characters standing for:

‘green colored dots with solid line’. By omitting the line part (‘-‘) in the

end, you will be left with only green dots (‘go’), which makes it draw a

scatterplot.

Few commonly used short hand format examples are:

* 'r*--' :

‘red stars with dashed lines’

* 'ks.' : ‘black squares with

dotted line’ (‘k’ stands for black)

* 'bD-.' : ‘blue diamonds

with dash-dot line’.

For a complete list of colors, markers and linestyles, check out the

help(plt.plot) command.

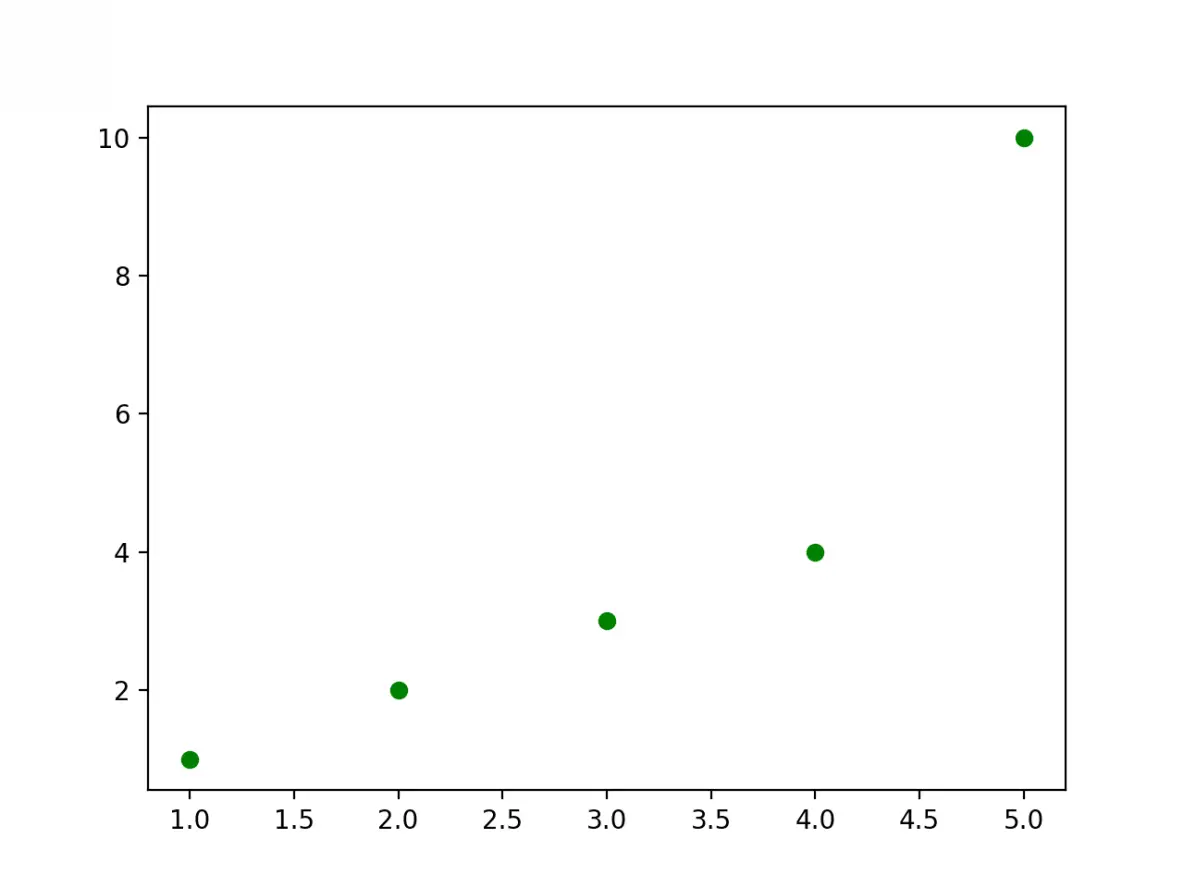

Let’s draw a scaterplot with greendots.

# 'go' stands for green dots

plt.plot([1,2,3,4,5], [1,2,3,4,10], 'go')

plt.show()

3. How to draw two

sets of scatterplots in same plot

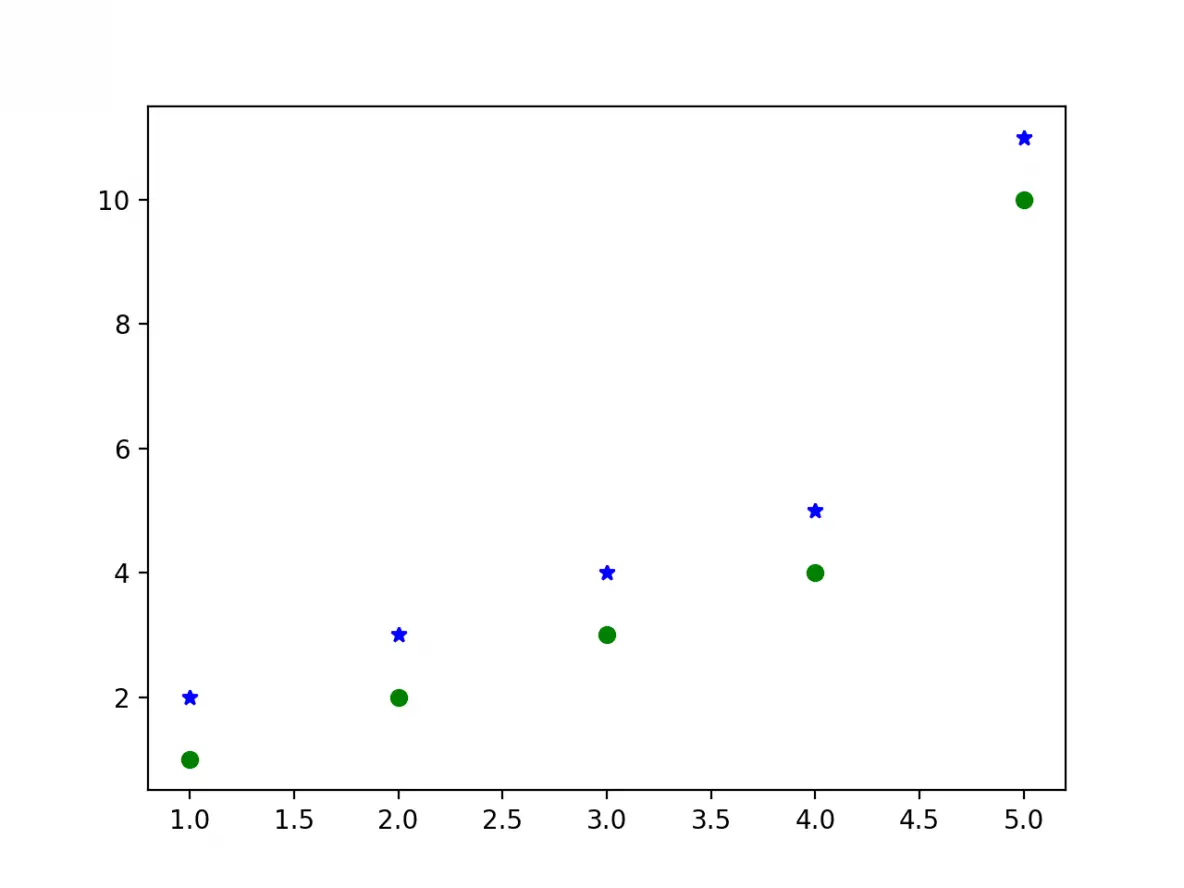

Good. Now how to plot another set of 5 points of different color in the same

figure?

Simply call plt.plot() again, it will add those point to the same

picture.

You might wonder, why it does not draw these points in a new panel

altogether? I will come to that in the next section.

# Draw two sets of points

plt.plot([1,2,3,4,5], [1,2,3,4,10], 'go') # green dots

plt.plot([1,2,3,4,5], [2,3,4,5,11], 'b*') # blue stars

plt.show()

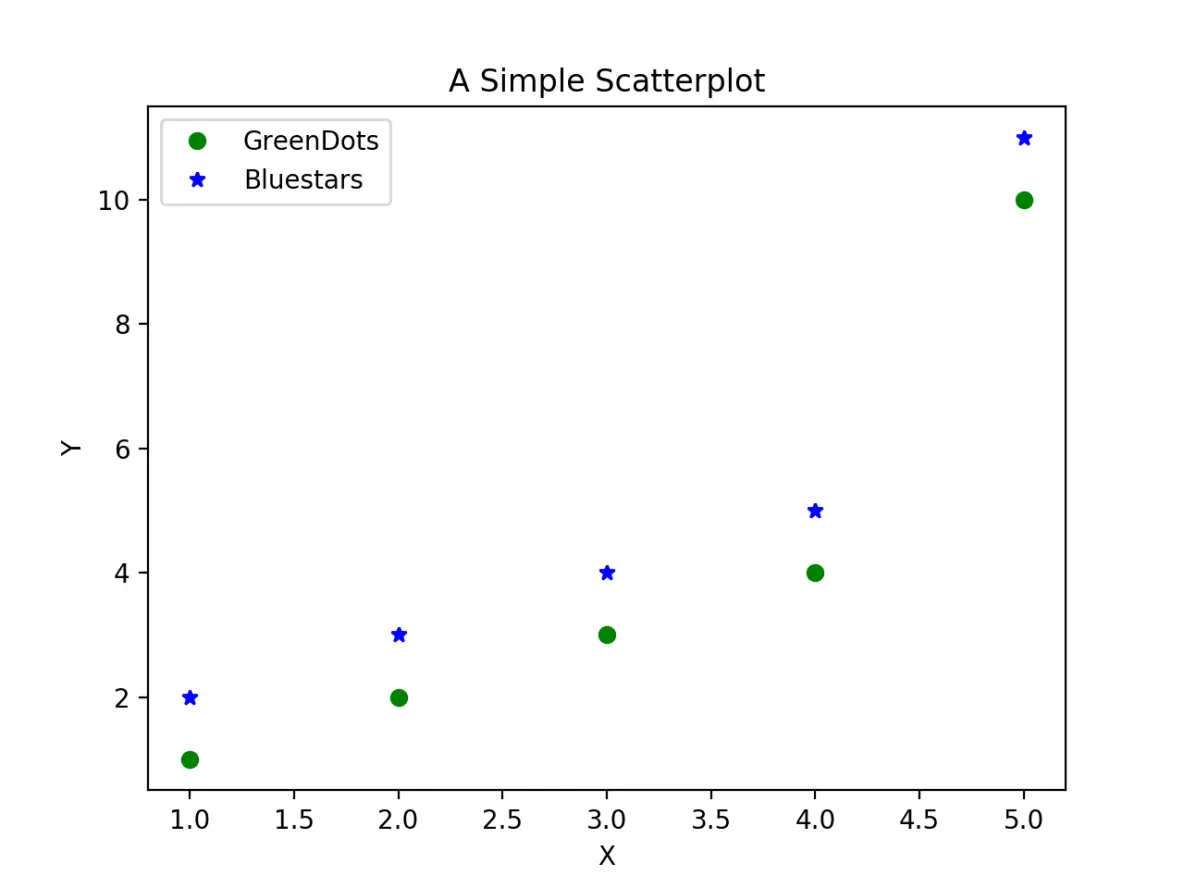

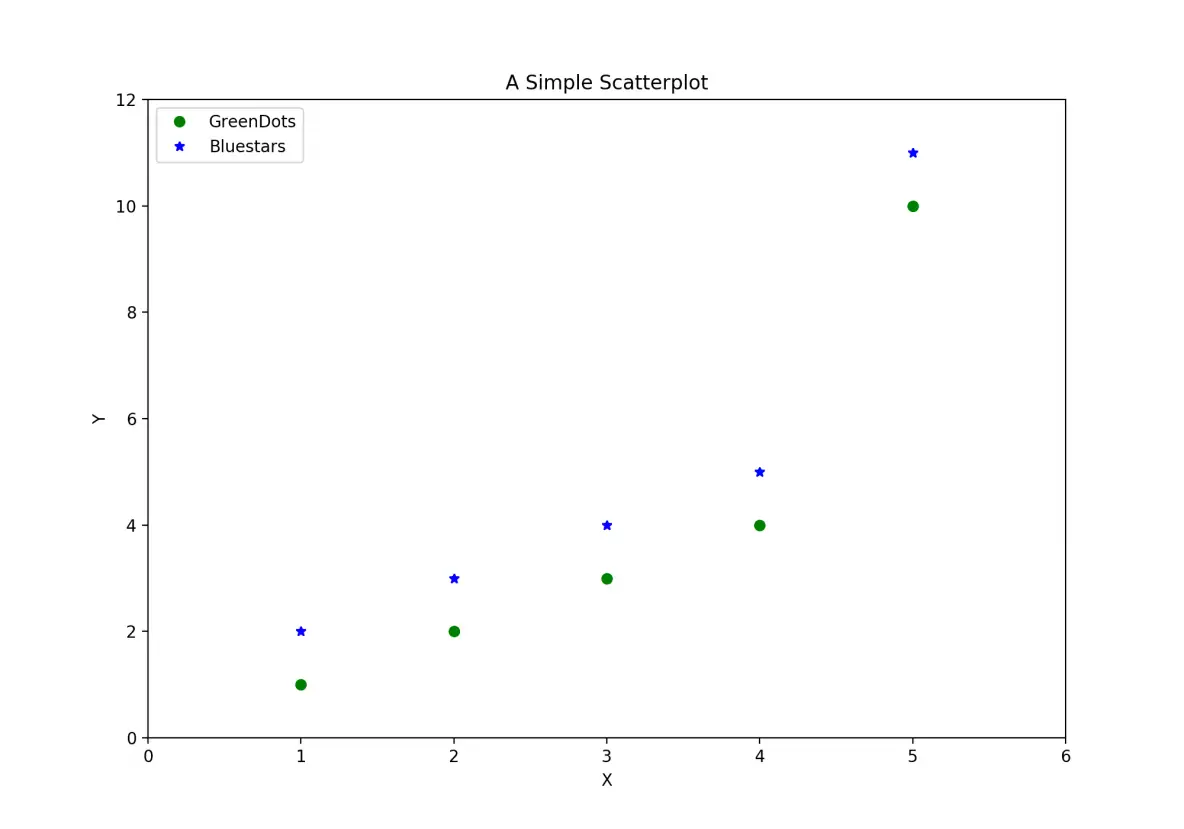

Looks good. Now let’s add the basic plot features: Title, Legend, X and Y

axis labels. How to do that?

The plt object has corresponding methods to add each of

this.

plt.plot([1,2,3,4,5], [1,2,3,4,10], 'go', label='GreenDots')

plt.plot([1,2,3,4,5], [2,3,4,5,11], 'b*', label='Bluestars')

plt.title('A Simple Scatterplot')

plt.xlabel('X')

plt.ylabel('Y')

plt.legend(loc='best') # legend text comes from the plot's label parameter.

plt.show()

Good. Now, how to increase the size of the plot? (The above plot would

actually look small on a jupyter notebook)

The easy way to do it is by setting the figsize inside

plt.figure() method.

plt.figure(figsize=(10,7)) # 10 is width, 7 is height

plt.plot([1,2,3,4,5], [1,2,3,4,10], 'go', label='GreenDots') # green dots

plt.plot([1,2,3,4,5], [2,3,4,5,11], 'b*', label='Bluestars') # blue stars

plt.title('A Simple Scatterplot')

plt.xlabel('X')

plt.ylabel('Y')

plt.xlim(0, 6)

plt.ylim(0, 12)

plt.legend(loc='best')

plt.show()

Ok, we have some new lines of code there. What does plt.figure

do?

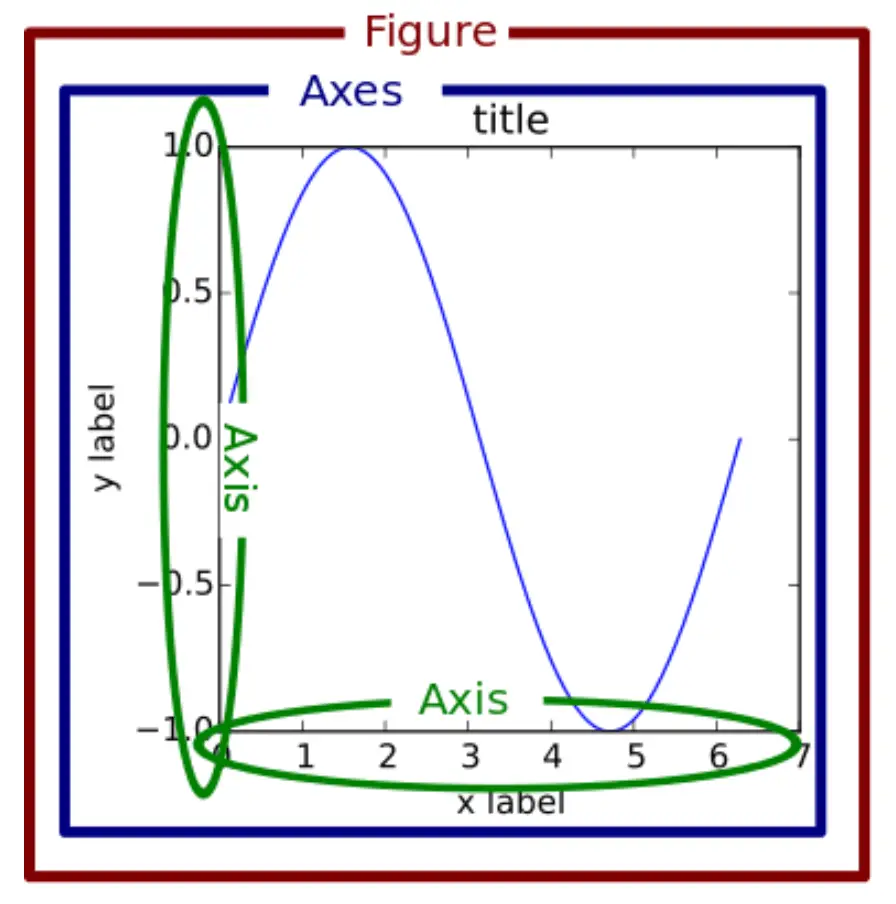

Well, every plot that matplotlib makes is drawn on something

called 'figure'. You can think of the figure object as

a canvas that holds all the subplots and other plot elements inside it.

And a figure can have one or more subplots inside it called

axes, arranged in rows and columns. Every figure has atleast one

axes. (Don’t confuse this axes with X and Y axis, they are

different.)

4. How to draw 2

scatterplots in different panels

Let’s understand figure and axes in little more

detail.

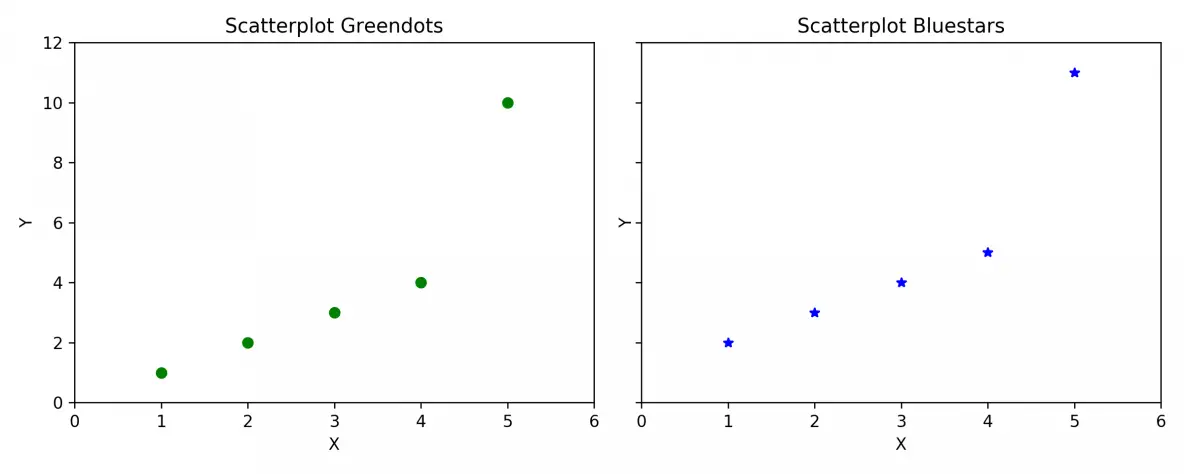

Suppose, I want to draw our two sets of points (green rounds and blue stars)

in two separate plots side-by-side instead of the same plot. How would you do

that?

You can do that by creating two separate subplots, aka, axes

using plt.subplots(1, 2). This creates and returns two

objects:

* the figure

* the axes (subplots) inside the figure

Previously, I called plt.plot() to draw the points. Since there

was only one axes by default, it drew the points on that axes itself.

But now, since you want the points drawn on different subplots (axes), you

have to call the plot function in the respective axes (ax1 and

ax2 in below code) instead of plt.

Notice in below code, I call ax1.plot() and

ax2.plot() instead of calling plt.plot() twice.

# Create Figure and

Subplots

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1,2, figsize=(10,4), sharey=True, dpi=120)

# Plot

ax1.plot([1,2,3,4,5], [1,2,3,4,10], 'go') # greendots

ax2.plot([1,2,3,4,5], [2,3,4,5,11], 'b*') # bluestart

# Title, X and Y labels, X and Y Lim

ax1.set_title('Scatterplot Greendots'); ax2.set_title('Scatterplot Bluestars')

ax1.set_xlabel('X'); ax2.set_xlabel('X') # x label

ax1.set_ylabel('Y'); ax2.set_ylabel('Y') # y label

ax1.set_xlim(0, 6) ; ax2.set_xlim(0, 6) # x axis limits

ax1.set_ylim(0, 12); ax2.set_ylim(0, 12) # y axis limits

# ax2.yaxis.set_ticks_position('none')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Setting sharey=True in plt.subplots() shares the Y

axis between the two subplots.

And dpi=120 increased the number of dots per inch of the plot to

make it look more sharp and clear. You will notice a distinct improvement in

clarity on increasing the dpi especially in jupyter notebooks.

Thats sounds like a lot of functions to learn. Well it’s quite easy to

remember it actually.

The ax1 and ax2 objects, like plt, has

equivalent set_title, set_xlabel and

set_ylabel functions. Infact, the plt.title() actually

calls the current axes set_title() to do the job.

- plt.xlabel() → ax.set_xlabel()

- plt.ylabel() → ax.set_ylabel()

- plt.xlim() → ax.set_xlim()

- plt.ylim() → ax.set_ylim()

- plt.title() → ax.set_title()

Alternately, to save keystrokes, you can set multiple things in one go using

the ax.set().

ax1.set(title='Scatterplot Greendots', xlabel='X', ylabel='Y', xlim=

(0,6), ylim=(0,12))

ax2.set(title='Scatterplot Bluestars', xlabel='X', ylabel='Y', xlim=(0,6), ylim=(0,12))

5. Object Oriented Syntax vs Matlab like Syntax

A known ‘problem’ with learning matplotlib is, it has two coding

interfaces:

- Matlab like syntax

- Object oriented syntax.

This is partly the reason why matplotlib doesn’t have one consistent way of

achieving the same given output, making it a bit difficult to understand for new

comers.

The syntax you’ve seen so far is the Object-oriented syntax, which I

personally prefer and is more intuitive and pythonic to work with.

However, since the original purpose of matplotlib was to recreate the

plotting facilities of matlab in python, the matlab-like-syntax is retained and

still works.

The matlab syntax is ‘stateful’.

That means, the plt keeps track of what the current

axes is. So whatever you draw with plt.{anything} will

reflect only on the current subplot.

Practically speaking, the main difference between the two syntaxes is, in

matlab-like syntax, all plotting is done using plt methods instead

of the respective axes‘s method as in object oriented syntax.

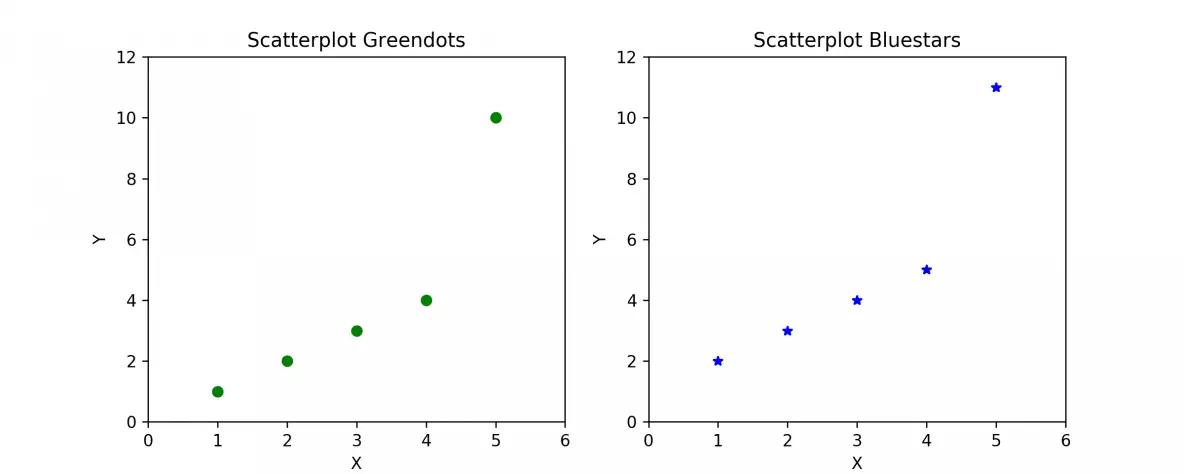

So, how to recreate the above multi-subplots figure (or any other figure for

that matter) using matlab-like syntax?

The general procedure is: You manually create one subplot at a time (using

plt.subplot() or plt.add_subplot()) and immediately

call plt.plot() or plt.{anything} to modify that

specific subplot (axes). Whatever method you call using plt will be

drawn in the current axes.

The code below shows this in practice.

plt.figure(figsize=(10,4), dpi=120) # 10 is width, 4 is

height

# Left hand side plot

plt.subplot(1,2,1) # (nRows, nColumns, axes number to plot)

plt.plot([1,2,3,4,5], [1,2,3,4,10], 'go') # green dots

plt.title('Scatterplot Greendots')

plt.xlabel('X'); plt.ylabel('Y')

plt.xlim(0, 6); plt.ylim(0, 12)

# Right hand side plot

plt.subplot(1,2,2)

plt.plot([1,2,3,4,5], [2,3,4,5,11], 'b*') # blue stars

plt.title('Scatterplot Bluestars')

plt.xlabel('X'); plt.ylabel('Y')

plt.xlim(0, 6); plt.ylim(0, 12)

plt.show()

Let’s breakdown the above piece of code.

In plt.subplot(1,2,1), the first two values, that is (1,2)

specifies the number of rows (1) and columns (2) and the third parameter (1)

specifies the position of current subplot. The subsequent plt

functions, will always draw on this current subplot.

You can get a reference to the current (subplot) axes with

plt.gca() and the current figure with plt.gcf().

Likewise, plt.cla() and plt.clf() will clear the

current axes and figure respectively.

Alright, compare the above code with the object oriented (OO) version. The OO

version might look a but confusing because it has a mix of both ax1

and plt commands.

However, there is a significant advantage with axes

approach.

That is, since plt.subplots returns all the axes as separate

objects, you can avoid writing repetitive code by looping through the axes.

Always remember: plt.plot() or plt.{anything} will

always act on the plot in the current axes, whereas,

ax.{anything} will modify the plot inside that specific

ax.

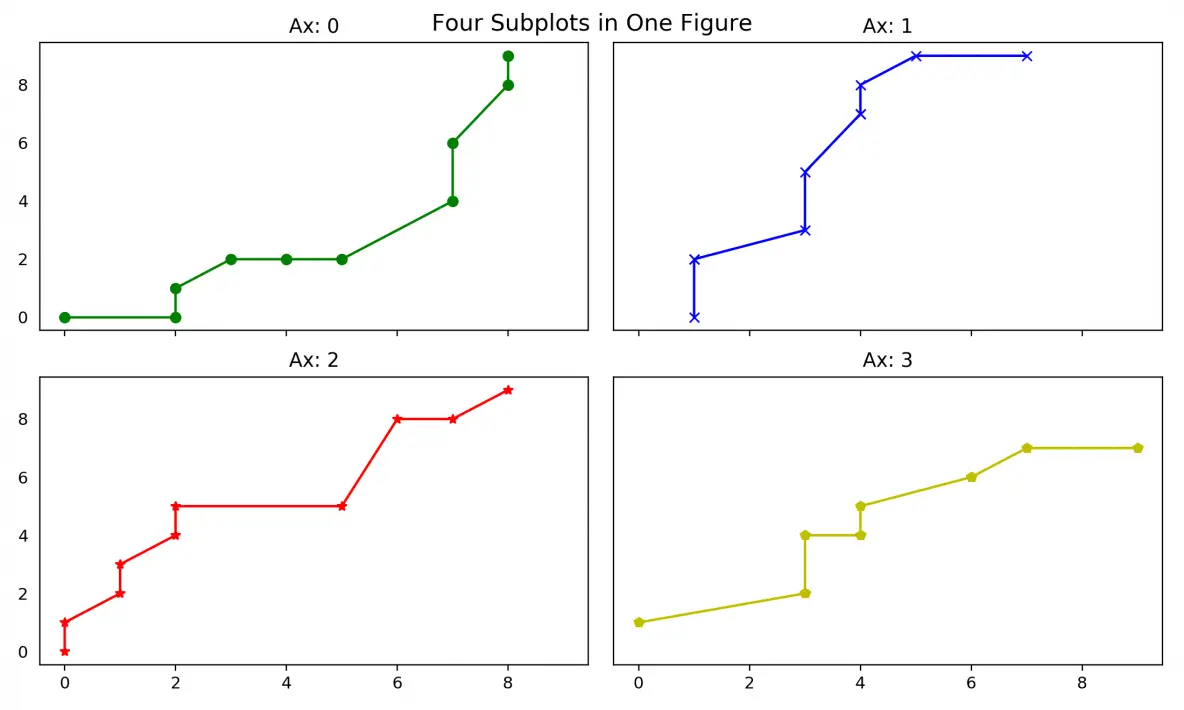

# Draw multiple plots using for-loops using object oriented syntax

import numpy as np

from numpy.random import seed, randint

seed(100)

# Create Figure and Subplots

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2,2, figsize=(10,6), sharex=True, sharey=True, dpi=120)

# Define the colors and markers to use

colors = {0:'g', 1:'b', 2:'r', 3:'y'}

markers = {0:'o', 1:'x', 2:'*', 3:'p'}

# Plot each axes

for i, ax in enumerate(axes.ravel()):

ax.plot(sorted(randint(0,10,10)), sorted(randint

(0,10,10)), marker=markers[(i)], color=colors[(i)])

ax.set_title('Ax: ' + str(i))

ax.yaxis.set_ticks_position('none')

plt.suptitle('Four Subplots in One Figure', verticalalignment='bottom', fontsize=16)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Did you notice in above plot, the Y-axis does not have ticks?

That’s because I used ax.yaxis.set_ticks_position('none') to

turn off the Y-axis ticks. This is another advantage of the object-oriented

interface. You can actually get a reference to any specific element of the plot

and use its methods to manipulate it.

Can you guess how to turn off the X-axis ticks?

The plt.suptitle() added a main title at figure level title.

plt.title() would have done the same for the current subplot

(axes).

The verticalalignment='bottom' parameter denotes the hingepoint

should be at the bottom of the title text, so that the main title is pushed

slightly upwards.

Alright, What you’ve learned so far is the core essence of how to create a

plot and manipulate it using matplotlib. Next, let’s see how to get the

reference to and modify the other components of the plot

6. How to Modify

the Axis Ticks Positions and Labels

There are 3 basic things you will probably ever need in matplotlib when it

comes to manipulating axis ticks:

1. How to control the position and tick

labels? (using plt.xticks() or ax.setxticks() and

ax.setxticklabels())

2. How to control which axis’s ticks

(top/bottom/left/right) should be displayed (using plt.tick_params())

3.

Functional formatting of tick labels

If you are using ax syntax, you can use

ax.set_xticks() and ax.set_xticklabels() to set the

positions and label texts respectively. If you are using the plt

syntax, you can set both the positions as well as the label text in one call

using the plt.xticks().

Actually, if you look at the code of plt.xticks() method (by

typing ??plt.xticks in jupyter notebook), it calls

ax.set_xticks() and ax.set_xticklabels() to do the

job. plt.xticks takes the ticks and

labels as required parameters but you can also adjust the label’s

fontsize, rotation, ‘horizontalalignment’ and

‘verticalalignment’ of the hinge points on the labels, like I’ve done in the

below example.

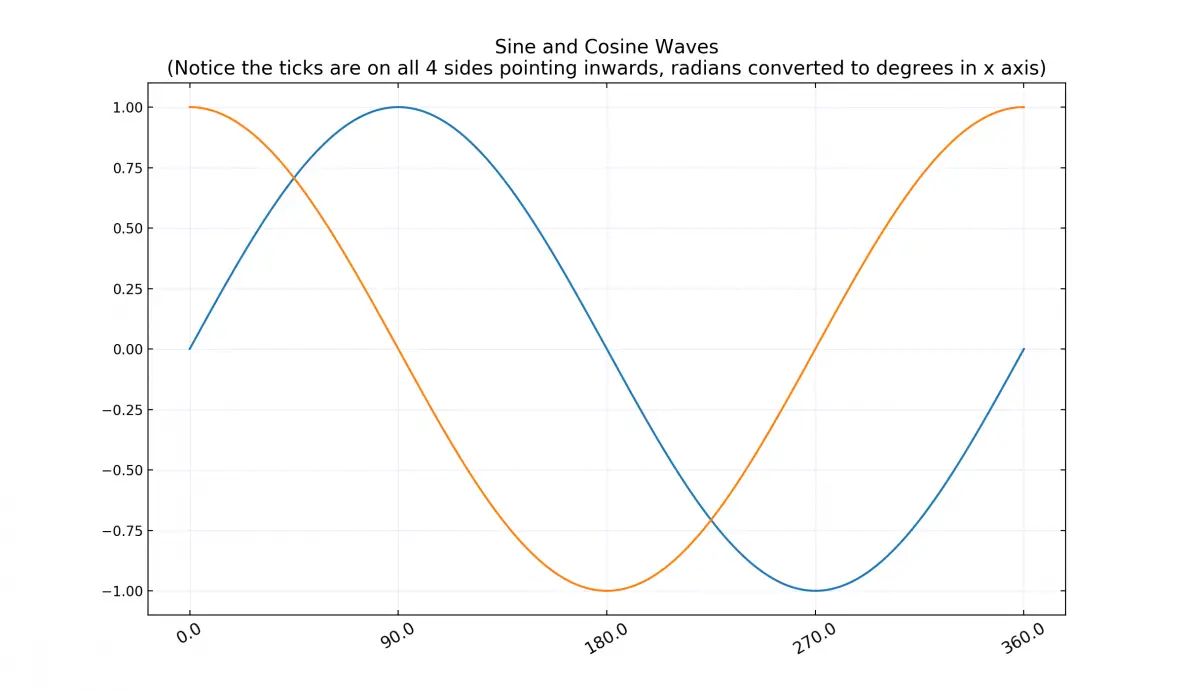

from matplotlib.ticker import FuncFormatter

def rad_to_degrees(x, pos):

'converts radians to degrees'

return round(x * 57.2985, 2)

plt.figure(figsize=(12,7), dpi=100)

X = np.linspace(0,2*np.pi,1000)

plt.plot(X,np.sin(X))

plt.plot(X,np.cos(X))

# 1. Adjust x axis Ticks

plt.xticks(ticks=np.arange(0, 440/57.2985, 90/57.2985), fontsize=12, rotation=30, ha='center',

va='top') # 1 radian = 57.2985 degrees

# 2. Tick Parameters

plt.tick_params(axis='both',bottom=True, top=True, left=True, right=True, direction='in',

which='major', grid_color='blue')

# 3. Format tick labels to convert radians to degrees

formatter = FuncFormatter(rad_to_degrees)

plt.gca().xaxis.set_major_formatter(formatter)

plt.grid(linestyle='--', linewidth=0.5, alpha=0.15)

plt.title('Sine and Cosine Waves\n(Notice the ticks are on all 4 sides pointing inwards, radians

converted to degrees in x axis)',

fontsize=14)

plt.show()

In above code, plt.tick_params() is used to determine which all

axis of the plot (‘top’ / ‘bottom’ / ‘left’ / ‘right’) you want to draw the

ticks and which direction (‘in’ / ‘out’) the tick should point to.

the matplotlib.ticker module provides the

FuncFormatter to determine how the final tick label should be

shown.

7. Understanding

the rcParams, Colors and Plot Styles

The look and feel of various components of a matplotlib plot can be set

globally using rcParams. The complete list of rcParams

can be viewed by typing:

mpl.rc_params()

# RcParams({'_internal.classic_mode': False,

# 'agg.path.chunksize': 0,

# 'animation.avconv_args': [],

# 'animation.avconv_path': 'avconv',

# 'animation.bitrate': -1,

# 'animation.codec': 'h264',

# ... TRUNCATED LaRge OuTPut ...

You can adjust the params you’d like to change by updating it. The below

snippet adjusts the font by setting it to ‘stix’, which looks great on plots by

the way.

mpl.rcParams.update({'font.size': 18, 'font.family': 'STIXGeneral', 'mathtext.fontset':

'stix'})

After modifying a plot, you can rollback the rcParams to default setting

using:

mpl.rcParams.update(mpl.rcParamsDefault) # reset to defaults

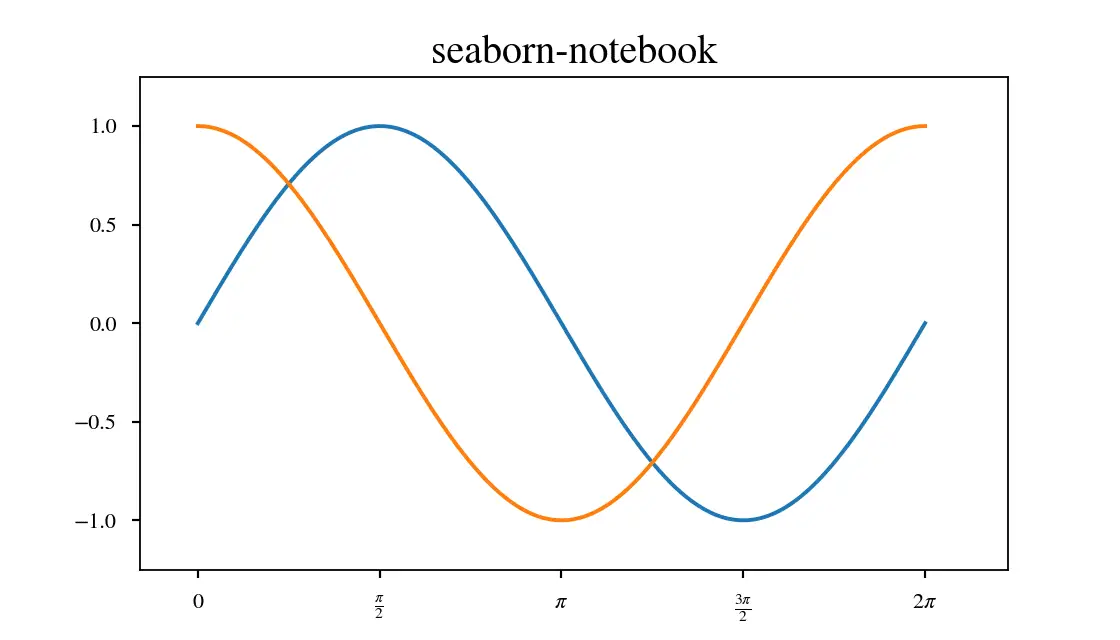

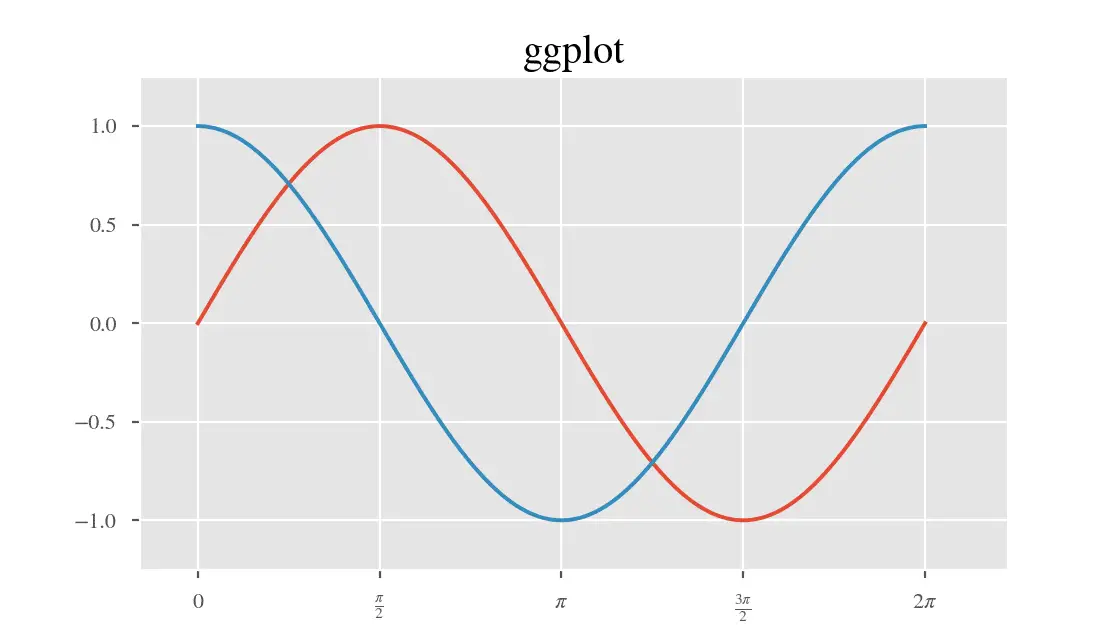

Matplotlib comes with pre-built styles which you can look by typing:

plt.style.available

# ['seaborn-dark', 'seaborn-darkgrid', 'seaborn-ticks', 'fivethirtyeight',

# 'seaborn-whitegrid', 'classic', '_classic_test', 'fast', 'seaborn-talk',

# 'seaborn-dark-palette', 'seaborn-bright', 'seaborn-pastel', 'grayscale',

# 'seaborn-notebook', 'ggplot', 'seaborn-colorblind', 'seaborn-muted',

# 'seaborn', 'Solarize_Light2', 'seaborn-paper', 'bmh', 'tableau-colorblind10',

# 'seaborn-white', 'dark_background', 'seaborn-poster', 'seaborn-deep']

import matplotlib as mpl

mpl.rcParams.update({'font.size': 18, 'font.family': 'STIXGeneral', 'mathtext.fontset': 'stix'})

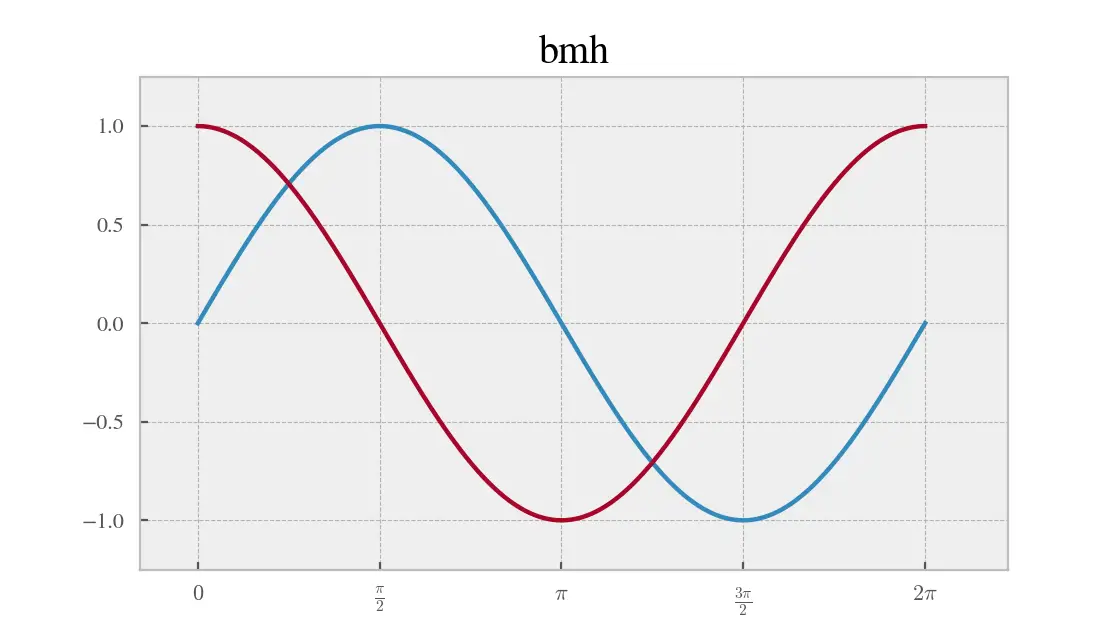

def plot_sine_cosine_wave(style='ggplot'):

plt.style.use(style)

plt.figure(figsize=(7,4), dpi=80)

X = np.linspace(0,2*np.pi,1000)

plt.plot(X,np.sin(X)); plt.plot(X,np.cos(X))

plt.xticks(ticks=np.arange(0, 440/57.2985, 90/57.2985),

labels = ['0','pi/2','pi','3*pi/2','2*pi']) # 1 radian = 57.2985 degrees

plt.gca().set(ylim=(-1.25, 1.25), xlim=(-.5, 7))

plt.title(style, fontsize=18)

plt.show()

plot_sine_cosine_wave('seaborn-notebook')

plot_sine_cosine_wave('ggplot')

plot_sine_cosine_wave('bmh')

I’ve just shown few of the pre-built styles, the rest of the list is

definitely worth a look.

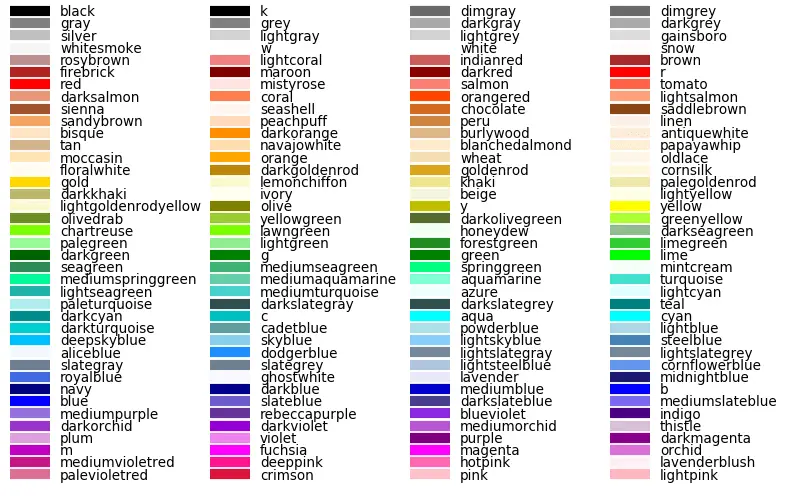

Matplotlib also comes with pre-built colors and palettes. Type the following

in your jupyter/python console to check out the available colors.

# View Colors

mpl.colors.CSS4_COLORS # 148 colors

mpl.colors.XKCD_COLORS # 949 colors

mpl.colors.BASE_COLORS # 8 colors

#> {'b': (0, 0, 1),

#> 'g': (0, 0.5, 0),

#> 'r': (1, 0, 0),

#> 'c': (0, 0.75, 0.75),

#> 'm': (0.75, 0, 0.75),

#> 'y': (0.75, 0.75, 0),

#> 'k': (0, 0, 0),

#> 'w': (1, 1, 1)}

# View first 10 Palettes

dir(plt.cm)[:10]

#> ['Accent', 'Accent_r', 'Blues', 'Blues_r',

#> 'BrBG', 'BrBG_r', 'BuGn', 'BuGn_r', 'BuPu', 'BuPu_r']

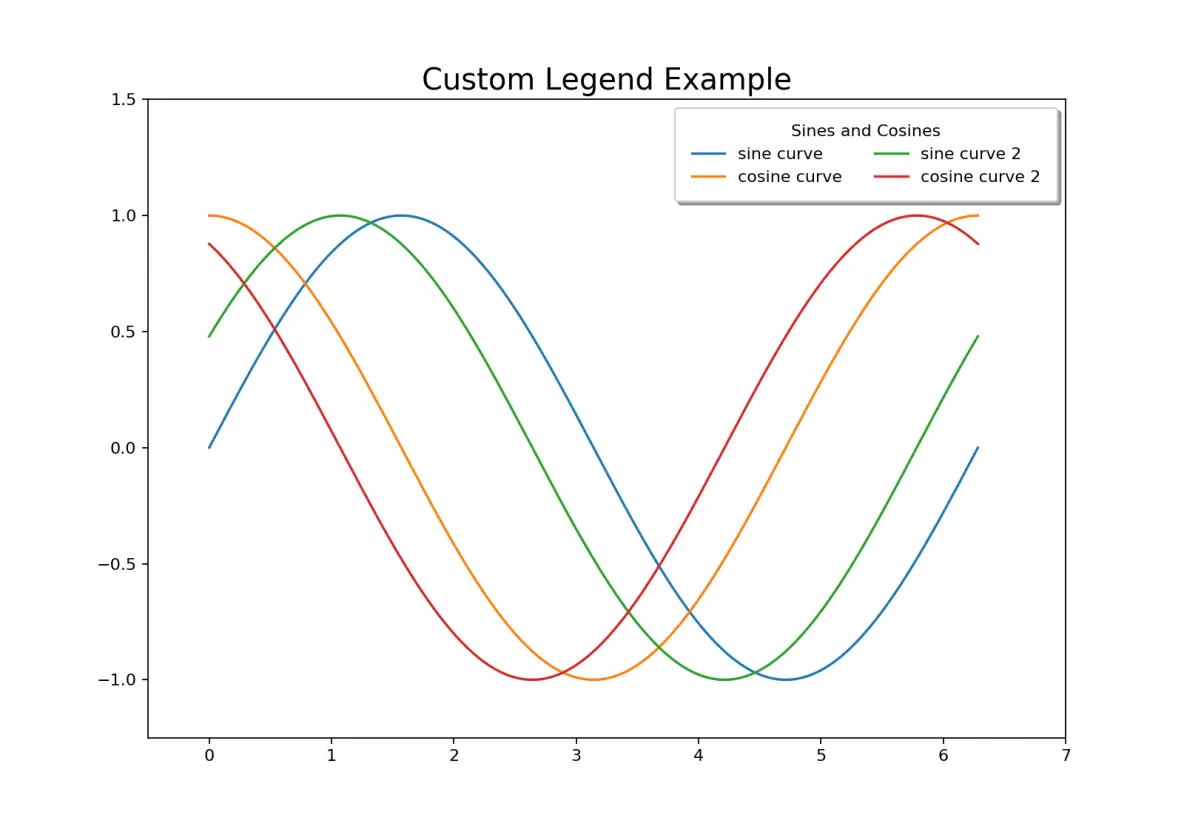

8. How to Customise the Legend

The most common way to make a legend is to define the label

parameter for each of the plots and finally call plt.legend().

However, sometimes you might want to construct the legend on your own. In

that case, you need to pass the plot items you want to draw the legend for and

the legend text as parameters to plt.legend() in the following

format:

plt.legend((line1, line2, line3), ('label1', 'label2',

'label3'))

# plt.style.use('seaborn-notebook')

plt.figure(figsize=(10,7), dpi=80)

X = np.linspace(0, 2*np.pi, 1000)

sine = plt.plot(X,np.sin(X)); cosine = plt.plot(X,np.cos(X))

sine_2 = plt.plot(X,np.sin(X+.5)); cosine_2 = plt.plot(X,np.cos(X+.5))

plt.gca().set(ylim=(-1.25, 1.5), xlim=(-.5, 7))

plt.title('Custom Legend Example', fontsize=18)

# Modify legend

plt.legend([sine[0], cosine[0], sine_2[0], cosine_2[0]], # plot items

['sine curve','cosine curve',

'sine curve 2','cosine curve 2'],

frameon=True, # legend border

framealpha=1, # transparency of border

ncol=2, # num columns

shadow=True, # shadow on

borderpad=1, # thickness of border

title='Sines and Cosines') # title

plt.show()

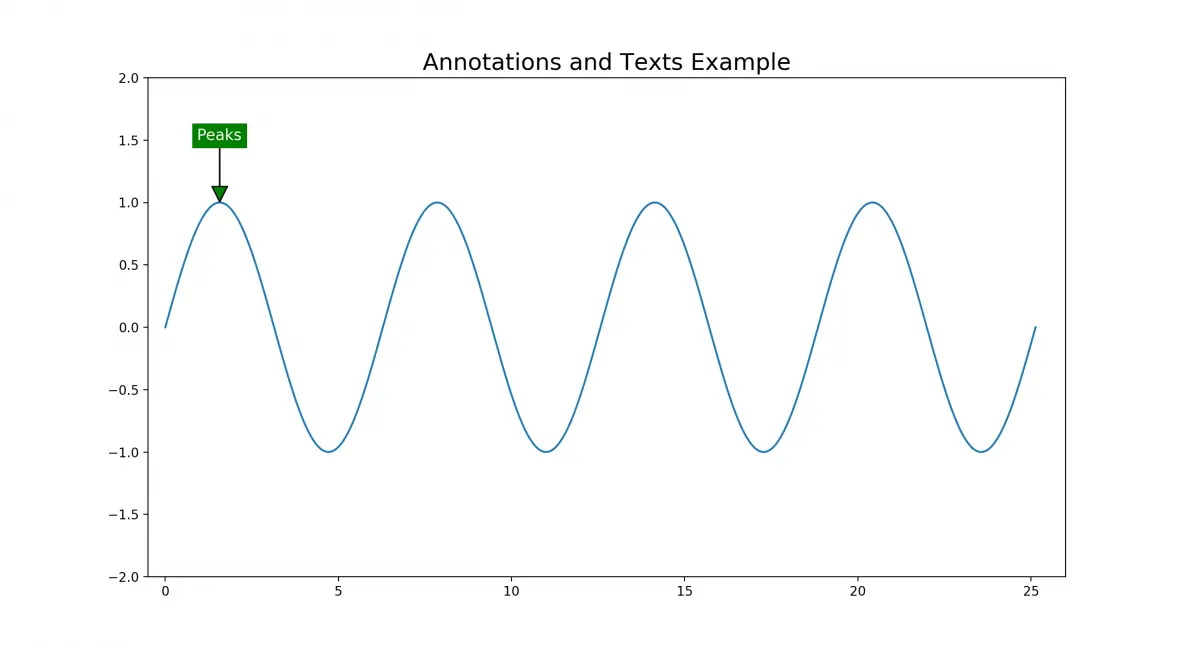

9. How to Add Texts, Arrows

and Annotations

plt.text and plt.annotate adds the texts and

annotations respectively. If you have to plot multiple texts you need to call

plt.text() as many times typically in a for-loop.

Let’s annotate the peaks and troughs adding arrowprops and a

bbox for the text.

# Texts, Arrows and Annotations Example

# ref: https://matplotlib.org/users/annotations_guide.html

plt.figure(figsize=(14,7), dpi=120)

X = np.linspace(0, 8*np.pi, 1000)

sine = plt.plot(X,np.sin(X), color='tab:blue');

# 1. Annotate with Arrow Props and bbox

plt.annotate('Peaks', xy=(90/57.2985, 1.0), xytext=(90/57.2985, 1.5),

bbox=dict(boxstyle='square', fc='green', linewidth=0.1),

arrowprops=dict(facecolor='green', shrink=0.01, width=0.1),

fontsize=12, color='white', horizontalalignment='center')

# 2. Texts at Peaks and Troughs

for angle in [440, 810, 1170]:

plt.text(angle/57.2985, 1.05, str(angle) + "\ndegrees",

transform=plt.gca().transData, horizontalalignment='center', color='green')

for angle in [270, 630, 990, 1350]:

plt.text(angle/57.2985, -1.3, str(angle) + "\ndegrees",

transform=plt.gca().transData,

horizontalalignment='center', color='red')

plt.gca().set(ylim=(-2.0, 2.0), xlim=(-.5, 26))

plt.title('Annotations and Texts Example', fontsize=18)

plt.show()

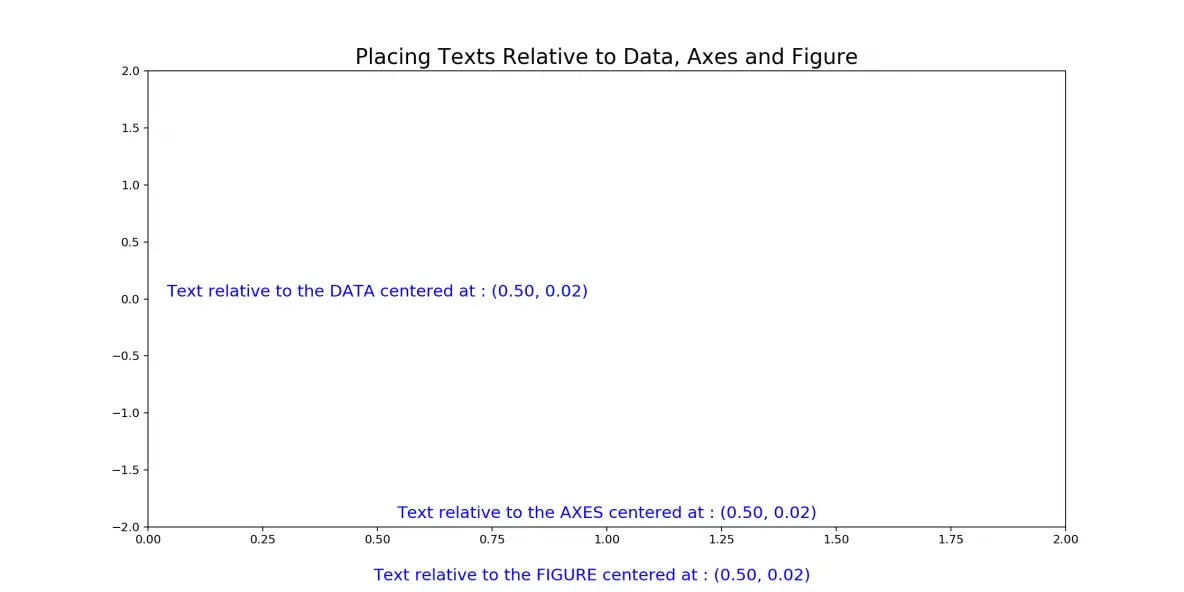

Notice, all the text we plotted above was in relation to the data.

That is, the x and y position in the plt.text() corresponds to

the values along the x and y axes. However, sometimes you might work with data

of different scales on different subplots and you want to write the texts in the

same position on all the subplots.

In such case, instead of manually computing the x and y positions for each

axes, you can specify the x and y values in relation to the axes (instead of x

and y axis values).

You can do this by setting transform=ax.transData.

The lower left corner of the axes has (x,y) = (0,0) and the top right corner

will correspond to (1,1).

The below plot shows the position of texts for the same values of (x,y) =

(0.50, 0.02) with respect to the Data(transData),

Axes(transAxes) and Figure(transFigure)

respectively.

# Texts, Arrows and Annotations Example

plt.figure(figsize=(14,7), dpi=80)

X = np.linspace(0, 8*np.pi, 1000)

# Text Relative to DATA

plt.text(0.50, 0.02, "Text relative to the DATA centered at : (0.50, 0.02)",

transform=plt.gca().transData, fontsize=14, ha='center',

color='blue')

# Text Relative to AXES

plt.text(0.50, 0.02, "Text relative to the AXES centered at : (0.50, 0.02)",

transform=plt.gca().transAxes, fontsize=14, ha='center',

color='blue')

# Text Relative to FIGURE

plt.text(0.50, 0.02, "Text relative to the FIGURE centered at : (0.50, 0.02)",

transform=plt.gcf().transFigure, fontsize=14, ha='center',

color='blue')

plt.gca().set(ylim=(-2.0, 2.0), xlim=(0, 2))

plt.title('Placing Texts Relative to Data, Axes and Figure', fontsize=18)

plt.show()

10. How to customize

matplotlib’s subplots layout

Matplotlib provides two convenient ways to create customized multi-subplots

layout.

plt.subplot2grid

plt.GridSpec

Both plt.subplot2grid and plt.GridSpec lets you

draw complex layouts. Below is a nice plt.subplot2grid example.

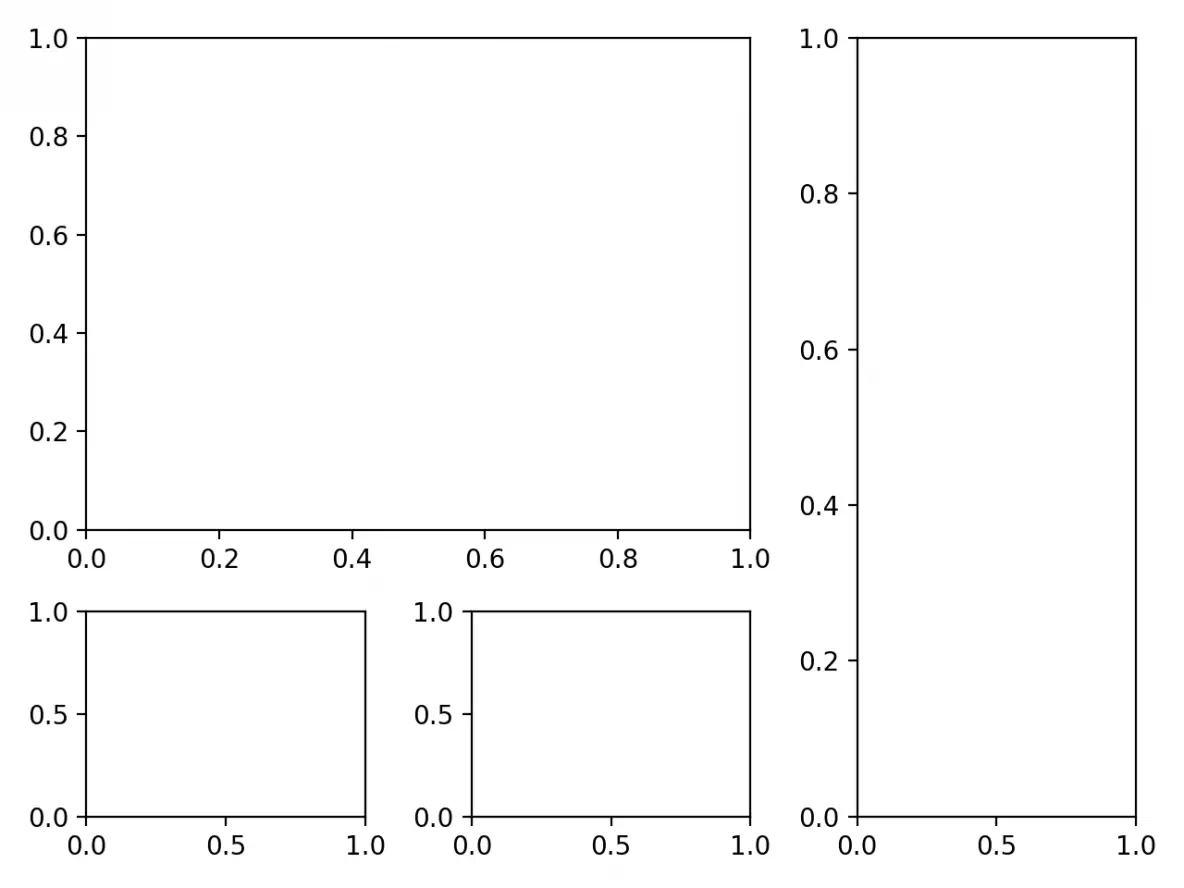

# Supplot2grid

approach

fig = plt.figure()

ax1 = plt.subplot2grid((3,3), (0,0), colspan=2, rowspan=2) # topleft

ax3 = plt.subplot2grid((3,3), (0,2), rowspan=3) # right

ax4 = plt.subplot2grid((3,3), (2,0)) # bottom left

ax5 = plt.subplot2grid((3,3), (2,1)) # bottom right

fig.tight_layout()

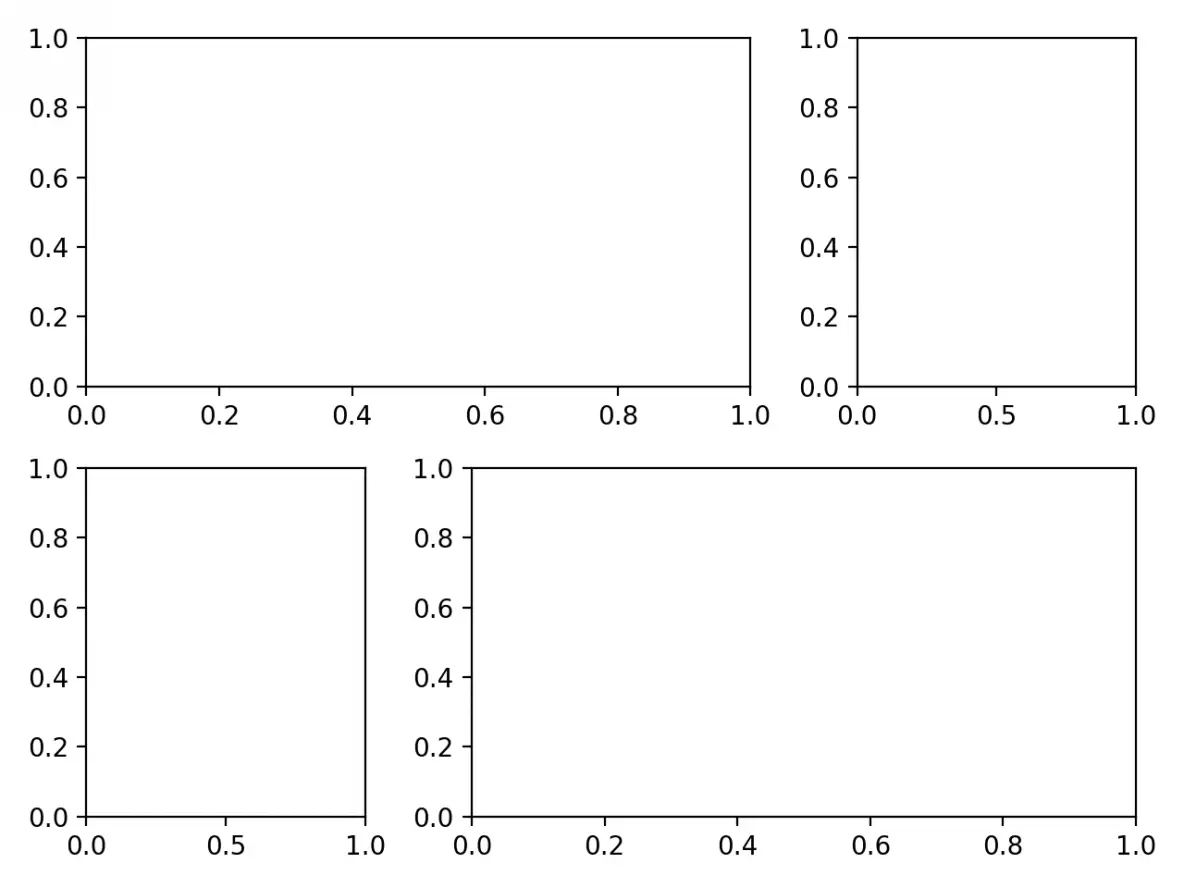

Using plt.GridSpec, you can use either a

plt.subplot() interface which takes part of the grid specified by

plt.GridSpec(nrow, ncol) or use the ax =

fig.add_subplot(g) where the GridSpec is defined by

height_ratios and weight_ratios.

# GridSpec Approach 1

import matplotlib.gridspec as gridspec

fig = plt.figure()

grid = plt.GridSpec(2, 3) # 2 rows 3 cols

plt.subplot(grid[0, :2]) # top left

plt.subplot(grid[0, 2]) # top right

plt.subplot(grid[1, :1]) # bottom left

plt.subplot(grid[1, 1:]) # bottom right

fig.tight_layout()

# GridSpec

Approach 2

import matplotlib.gridspec as gridspec

fig = plt.figure()

gs = gridspec.GridSpec(2, 2, height_ratios=[2,1], width_ratios=[1,2])

for g in gs:

ax = fig.add_subplot(g)

fig.tight_layout()

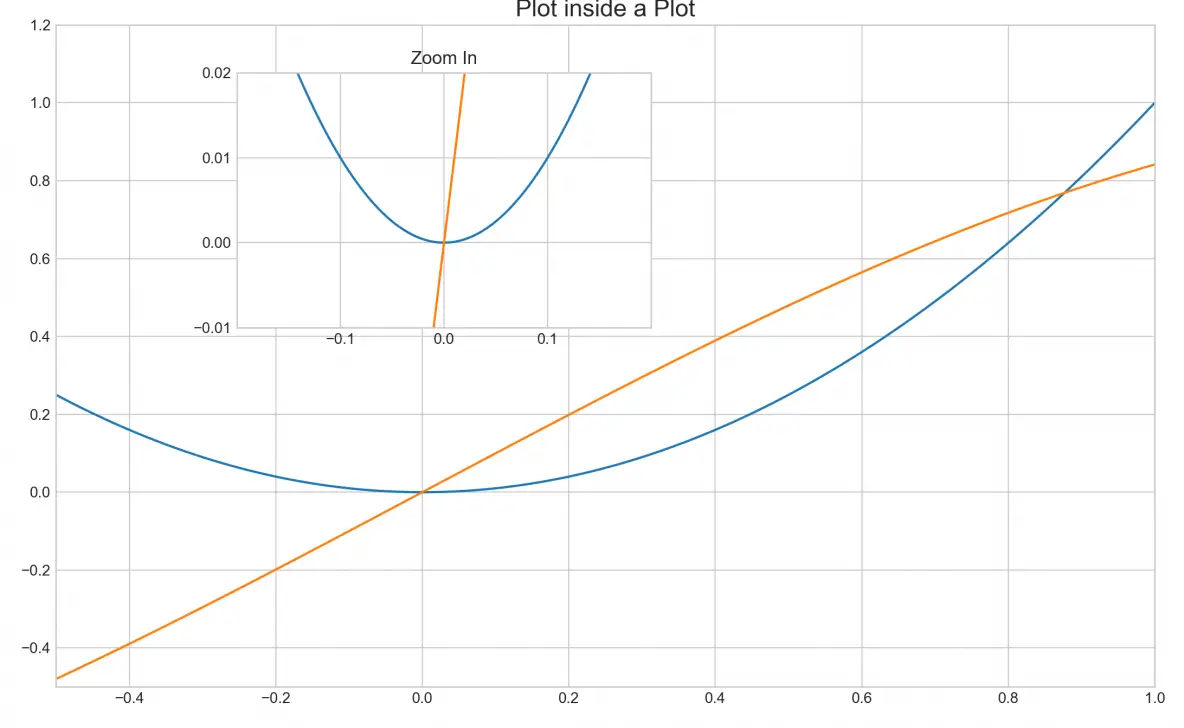

The above examples showed layouts where the subplots dont overlap. It is

possible to make subplots to overlap. Infact you can draw an axes

inside a larger axes using fig.add_axes(). You need to

specify the x,y positions relative to the figure and also the width and height

of the inner plot.

Below is an example of an inner plot that zooms in to a larger plot.

# Plot inside a plot

plt.style.use('seaborn-whitegrid')

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10,6))

x = np.linspace(-0.50, 1., 1000)

# Outer Plot

ax.plot(x, x**2)

ax.plot(x, np.sin(x))

ax.set(xlim=(-0.5, 1.0), ylim=(-0.5,1.2))

fig.tight_layout()

# Inner Plot

inner_ax = fig.add_axes([0.2, 0.55, 0.35, 0.35]) # x, y, width, height

inner_ax.plot(x, x**2)

inner_ax.plot(x, np.sin(x))

inner_ax.set(title='Zoom In', xlim=(-.2, .2), ylim=(-.01, .02),

yticks = [-0.01, 0, 0.01, 0.02], xticks=[-0.1,0,.1])

ax.set_title("Plot inside a Plot", fontsize=20)

plt.show()

mpl.rcParams.update(mpl.rcParamsDefault) # reset to defaults

11.

How is scatterplot drawn with plt.plot different from plt.scatter

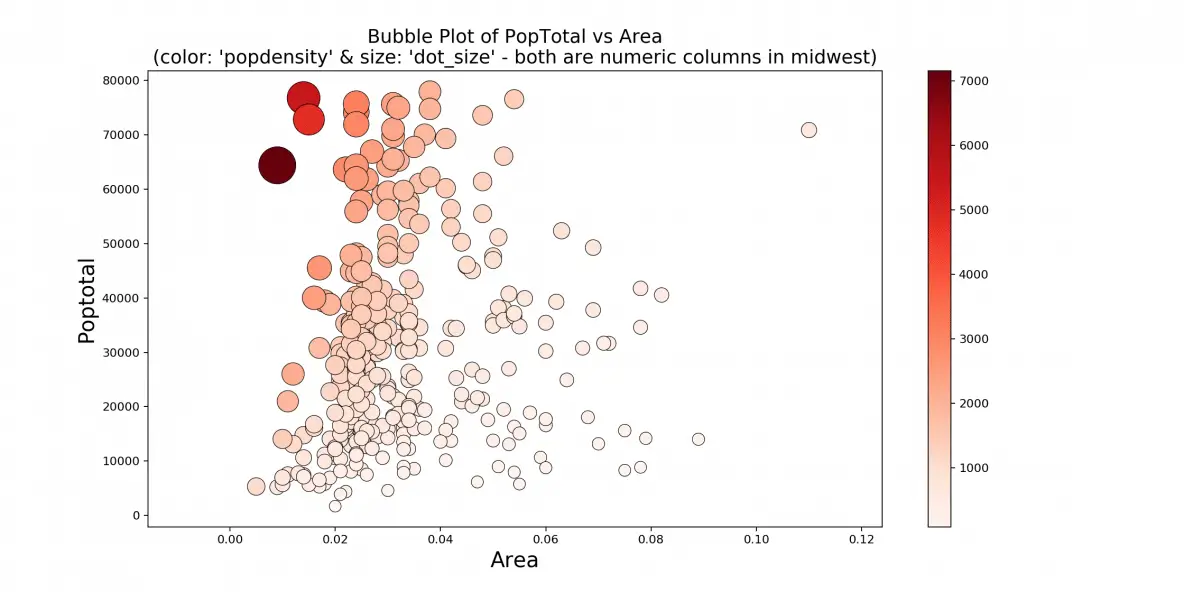

The difference is plt.plot() does not provide options to change

the color and size of point dynamically (based on another array). But

plt.scatter() allows you to do that.

By varying the size and color of points, you can create nice looking bubble

plots.

Another convenience is you can directly use a pandas dataframe to set the x

and y values, provided you specify the source dataframe in the data

argument.

You can also set the color 'c' and size 's' of the

points from one of the dataframe columns itself.

# Scatterplot with varying size and color of

points

import pandas as pd

midwest = pd.read_csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/selva86/datasets/master/midwest_filter.csv")

# Plot

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(14, 7), dpi= 80, facecolor='w', edgecolor='k')

plt.scatter('area', 'poptotal', data=midwest, s='dot_size', c='popdensity',

cmap='Reds', edgecolors='black', linewidths=.5)

plt.title("Bubble Plot of PopTotal vs Area\n(color: 'popdensity' & size: 'dot_size'

- both are numeric columns in midwest)",

fontsize=16)

plt.xlabel('Area', fontsize=18)

plt.ylabel('Poptotal', fontsize=18)

plt.colorbar()

plt.show()

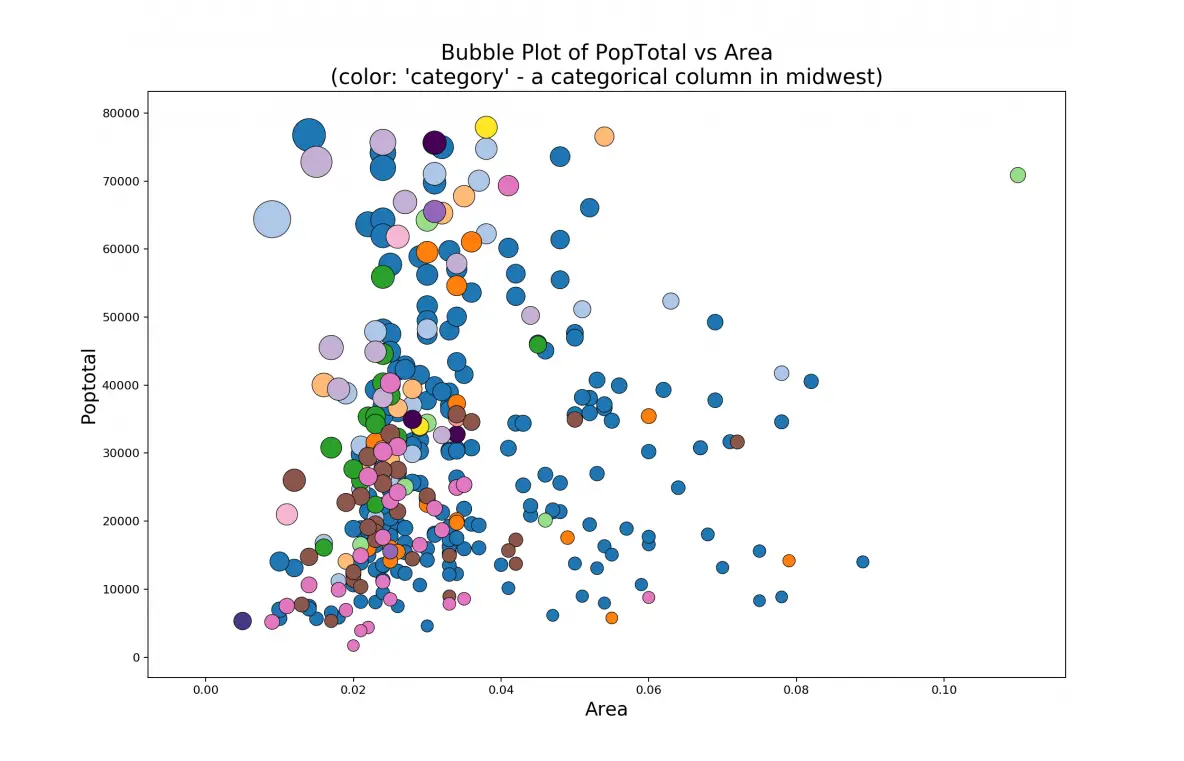

#

Import data

import pandas as pd

midwest = pd.read_csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/selva86/datasets/master/midwest_filter.csv")

# Plot

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(14, 9), dpi= 80, facecolor='w', edgecolor='k')

colors = plt.cm.tab20.colors

categories = np.unique(midwest['category'])

for i, category in enumerate(categories):

plt.scatter('area', 'poptotal',

data=midwest.loc[midwest.category==category, :], s='dot_size',

c=colors[(i)], label=str(category),

edgecolors='black', linewidths=.5)

# Legend for size of points

for dot_size in [100, 300, 1000]:

plt.scatter([], [], c='k', alpha=0.5, s=dot_size,

label=str(dot_size) + ' TotalPop')

plt.legend(loc='upper right', scatterpoints=1, frameon=False, labelspacing=2,

title='Saravana Stores', fontsize=8)

plt.title("Bubble Plot of PopTotal vs Area\n(color: 'category'

- a categorical column in midwest)", fontsize=18)

plt.xlabel('Area', fontsize=16)

plt.ylabel('Poptotal', fontsize=16)

plt.show()

# Save

the figure

plt.savefig("bubbleplot.png", transparent=True, dpi=120)

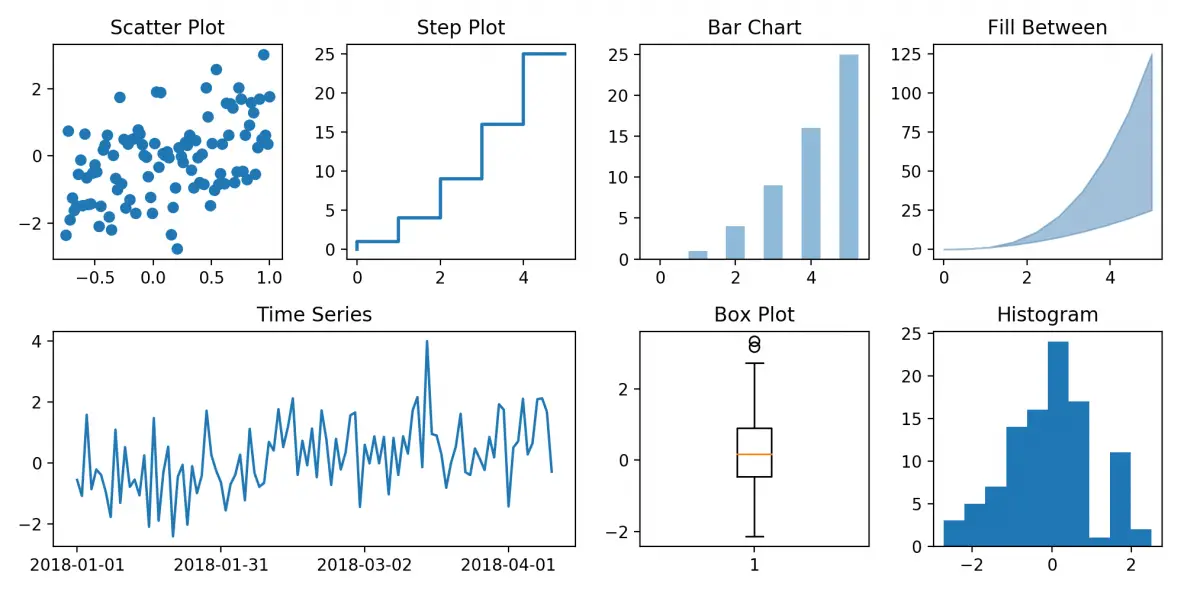

12. How to draw

Histograms, Boxplots and Time Series

The methods to draw different types of plots are present in pyplot

(plt) as well as Axes. The below example shows basic

examples of few of the commonly used plot types.

import pandas as pd

# Setup the subplot2grid Layout

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10, 5))

ax1 = plt.subplot2grid((2,4), (0,0))

ax2 = plt.subplot2grid((2,4), (0,1))

ax3 = plt.subplot2grid((2,4), (0,2))

ax4 = plt.subplot2grid((2,4), (0,3))

ax5 = plt.subplot2grid((2,4), (1,0), colspan=2)

ax6 = plt.subplot2grid((2,4), (1,2))

ax7 = plt.subplot2grid((2,4), (1,3))

# Input Arrays

n = np.array([0,1,2,3,4,5])

x = np.linspace(0,5,10)

xx = np.linspace(-0.75, 1., 100)

# Scatterplot

ax1.scatter(xx, xx + np.random.randn(len(xx)))

ax1.set_title("Scatter Plot")

# Step Chart

ax2.step(n, n**2, lw=2)

ax2.set_title("Step Plot")

# Bar Chart

ax3.bar(n, n**2, align="center", width=0.5, alpha=0.5)

ax3.set_title("Bar Chart")

# Fill Between

ax4.fill_between(x, x**2, x**3, color="steelblue", alpha=0.5);

ax4.set_title("Fill Between");

# Time Series

dates = pd.date_range('2018-01-01', periods = len(xx))

ax5.plot(dates, xx + np.random.randn(len(xx)))

ax5.set_xticks(dates[::30])

ax5.set_xticklabels(dates.strftime('%Y-%m-%d')[::30])

ax5.set_title("Time Series")

# Box Plot

ax6.boxplot(np.random.randn(len(xx)))

ax6.set_title("Box Plot")

# Histogram

ax7.hist(xx + np.random.randn(len(xx)))

ax7.set_title("Histogram")

fig.tight_layout()

What about more advanced plots?

If you want to see more data analysis oriented examples of a particular plot

type, say histogram or time series, the top

50 master plots for data analysis will give you concrete examples of

presentation ready plots. This is a very useful tool to have, not only to

construct nice looking plots but to draw ideas to what type of plot you want to

make for your data.

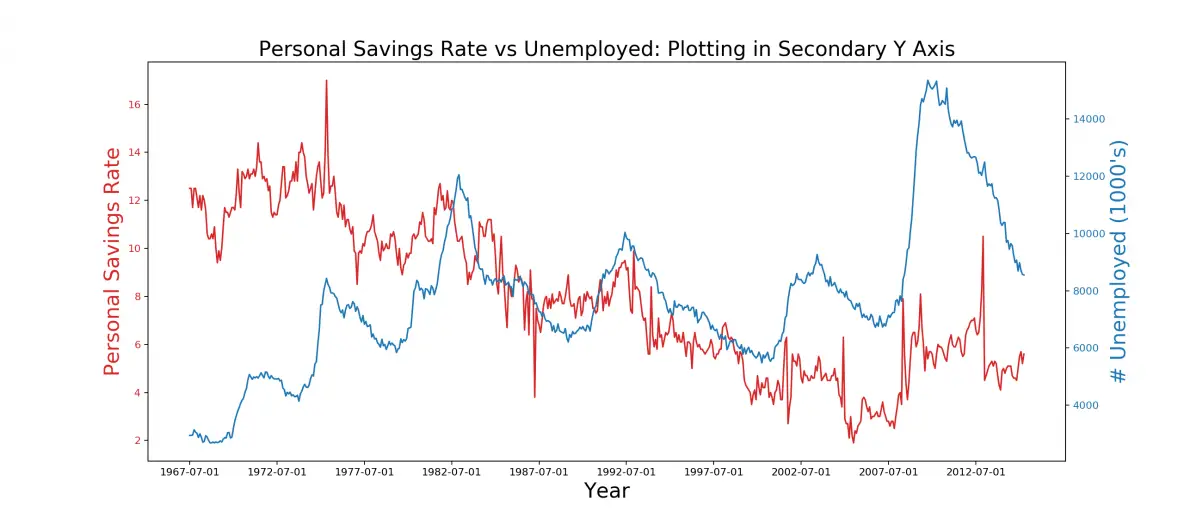

13. How to Plot with two Y-Axis

Plotting a line chart on the left-hand side axis is straightforward, which

you’ve already seen.

So how to draw the second line on the right-hand side y-axis?

The trick is to activate the right hand side Y axis using

ax.twinx() to create a second axes.

This second axes will have the Y-axis on the right activated and shares the

same x-axis as the original ax. Then, whatever you draw using this

second axes will be referenced to the secondary y-axis. The remaining job is to

just color the axis and tick labels to match the color of the lines.

# Import Data

df = pd.read_csv("https://github.com/selva86/datasets/raw/master/economics.csv")

x = df['date']; y1 = df['psavert']; y2 = df['unemploy']

# Plot Line1 (Left Y Axis)

fig, ax1 = plt.subplots(1,1,figsize=(16,7), dpi= 80)

ax1.plot(x, y1, color='tab:red')

# Plot Line2 (Right Y Axis)

ax2 = ax1.twinx() # instantiate a second axes that shares the same x-axis

ax2.plot(x, y2, color='tab:blue')

# Just Decorations!! -------------------

# ax1 (left y axis)

ax1.set_xlabel('Year', fontsize=20)

ax1.set_ylabel('Personal Savings Rate', color='tab:red', fontsize=20)

ax1.tick_params(axis='y', rotation=0, labelcolor='tab:red' )

# ax2 (right Y axis)

ax2.set_ylabel("# Unemployed (1000's)", color='tab:blue', fontsize=20)

ax2.tick_params(axis='y', labelcolor='tab:blue')

ax2.set_title("Personal Savings Rate vs Unemployed: Plotting in Secondary Y Axis", fontsize=20)

ax2.set_xticks(np.arange(0, len(x), 60))

ax2.set_xticklabels(x[::60], rotation=90, fontdict={'fontsize':10})

plt.show()

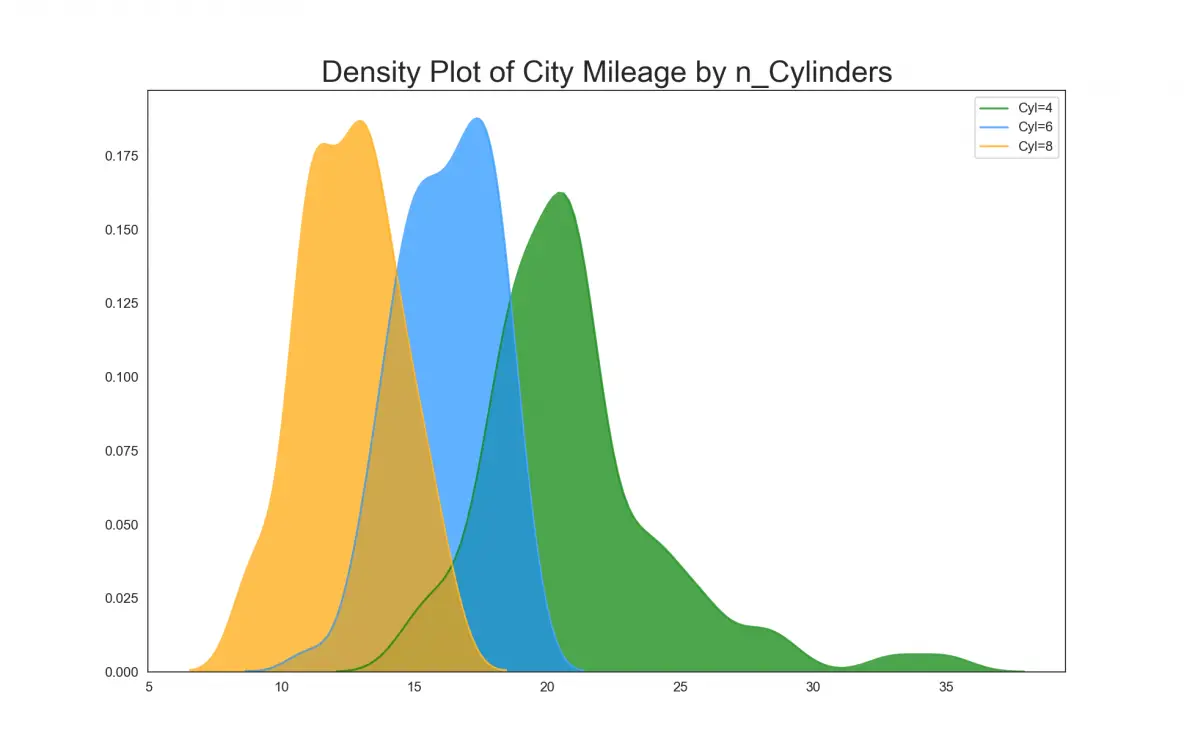

14. Introduction to Seaborn

As the charts get more complex, the more the code you’ve got to write. For

example, in matplotlib, there is no direct method to draw a density plot of a

scatterplot with line of best fit. You get the idea.

So, what you can do instead is to use a higher level package like seaborn,

and use one of its prebuilt functions to draw the plot.

We are not going in-depth into seaborn. But let’s see how to get started and

where to find what you want. A lot of seaborn’s plots are suitable for data

analysis and the library works seamlessly with pandas dataframes.

seaborn is typically imported as sns. Like

matplotlib it comes with its own set of pre-built styles and

palettes.

import seaborn as sns

sns.set_style("white")

# Import Data

df = pd.read_csv("https://github.com/selva86/datasets/raw/master/mpg_ggplot2.csv")

# Draw Plot

plt.figure(figsize=(16,10), dpi= 80)

sns.kdeplot(df.loc[df['cyl'] == 4, "cty"], shade=True, color="g", label="Cyl=4", alpha=.7)

sns.kdeplot(df.loc[df['cyl'] == 6, "cty"], shade=True, color="dodgerblue", label="Cyl=6", alpha=.7)

sns.kdeplot(df.loc[df['cyl'] == 8, "cty"], shade=True, color="orange", label="Cyl=8", alpha=.7)

# Decoration

plt.title('Density Plot of City Mileage by n_Cylinders', fontsize=22)

plt.legend()

plt.show()

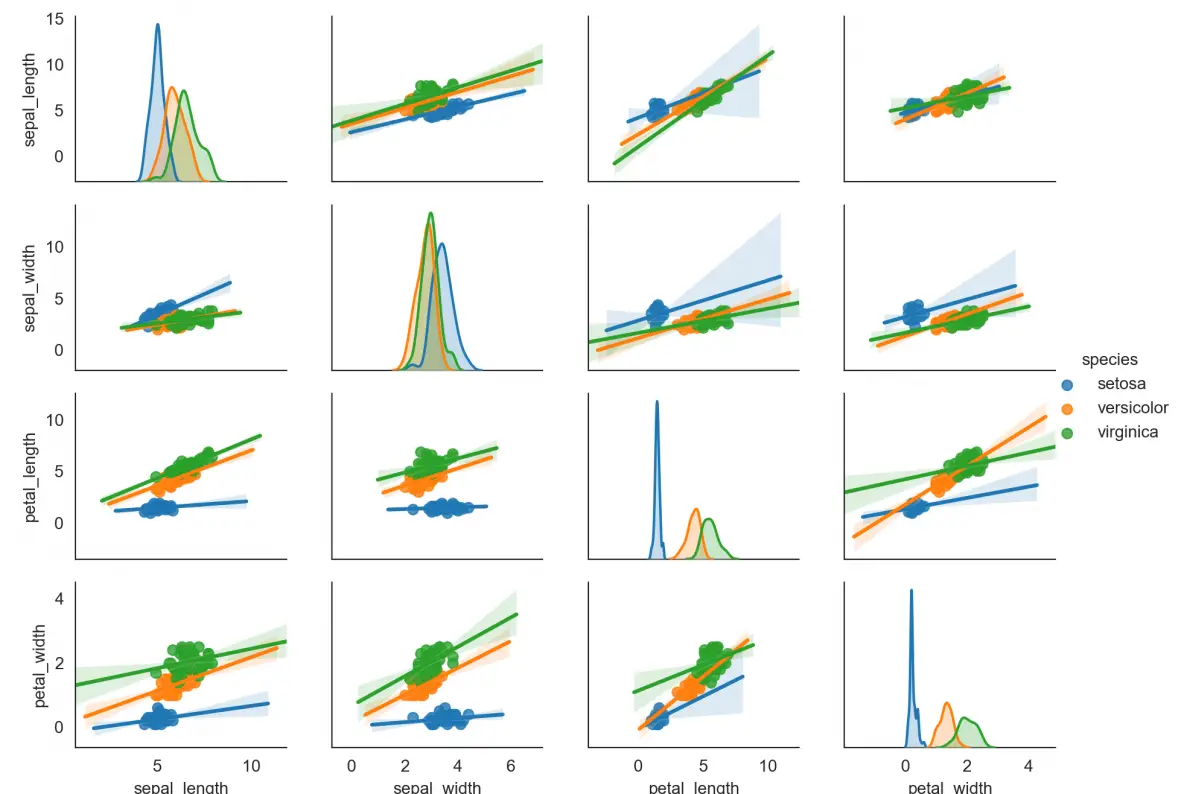

# Load

Dataset

df = sns.load_dataset('iris')

# Plot

plt.figure(figsize=(10,8), dpi= 80)

sns.pairplot(df, kind="reg", hue="species")

plt.show()

<Figure size 800x640 with 0 Axes>

This is just to give a hint of what’s possible with seaborn. Maybe I will

write a separate post on it. However, the official seaborn page has good examples for you to start

with.

15. Conclusion

Congratulations if you reached this far. Because we literally started from

scratch and covered the essential topics to making matplotlib plots.

We covered the syntax and overall structure of creating matplotlib plots, saw

how to modify various components of a plot, customized subplots layout, plots

styling, colors, palettes, draw different plot types etc.

If you want to get more practice, try taking up couple of plots listed in the

top

50 plots starting with correlation plots and try recreating it.

Until next time!